Staring at a set of arterial blood gas (ABG) values can feel like you're trying to decipher a secret code. But with a structured approach, the chaos quickly turns into a clear clinical picture. The key is a repeatable method: check the pH, find the primary respiratory or metabolic driver, and then see how the body is trying to compensate.

This simple algorithm is what turns a confusing jumble of numbers into a coherent physiological story.

Your Systematic Approach to ABG Interpretation

Trying to interpret an ABG without a system is a recipe for disaster, especially on the wards or during an exam. The goal isn't just memorizing numbers; it's about building a diagnostic framework that you can rely on every single time. A solid method sharpens your clinical reasoning and gives you a much deeper understanding of what's really going on with your patient.

Every reliable interpretation starts with the most fundamental question: is the patient's blood acidic or alkaline? That first step dictates everything that follows.

First, Look at the pH

Before you look at anything else, find the pH. This one number immediately tells you if the patient is in a state of acidemia (pH < 7.35)** or **alkalemia (pH > 7.45). Think of the pH as the headline of the story; everything else you uncover is just filling in the details of how the patient got there.

A word of caution: if the pH is smack in the middle of the normal range (7.35-7.45), don't get complacent. It could mean everything is fine, or it could signal a fully compensated mixed disorder where two opposing problems are masking each other.

Key Takeaway: The pH is your compass. It points you toward the overall acid-base status and guides every subsequent step of your analysis. Never move on until you've classified the pH.

Find the Primary Problem

Once you've established acidemia or alkalemia, your next job is to hunt down the cause. You'll look at the PaCO2 (the respiratory piece) and the HCO3- (the metabolic piece) to see which one is moving in a way that explains the pH.

The mnemonic ROME (Respiratory Opposite, Metabolic Equal) is a lifesaver here.

- Respiratory Opposite: If the pH is low (acidosis) and the PaCO2 is high, the problem is respiratory. The values are moving in opposite directions.

- Metabolic Equal: If the pH is low (acidosis) and the HCO3- is also low, the problem is metabolic. The values are moving in the same, or equal, direction.

This quick check is an incredibly reliable way to pinpoint the primary disturbance. Understanding complex diagnostics like this is a cornerstone of medicine, and if you're exploring career paths, it's worth thinking about why study healthcare professional courses.

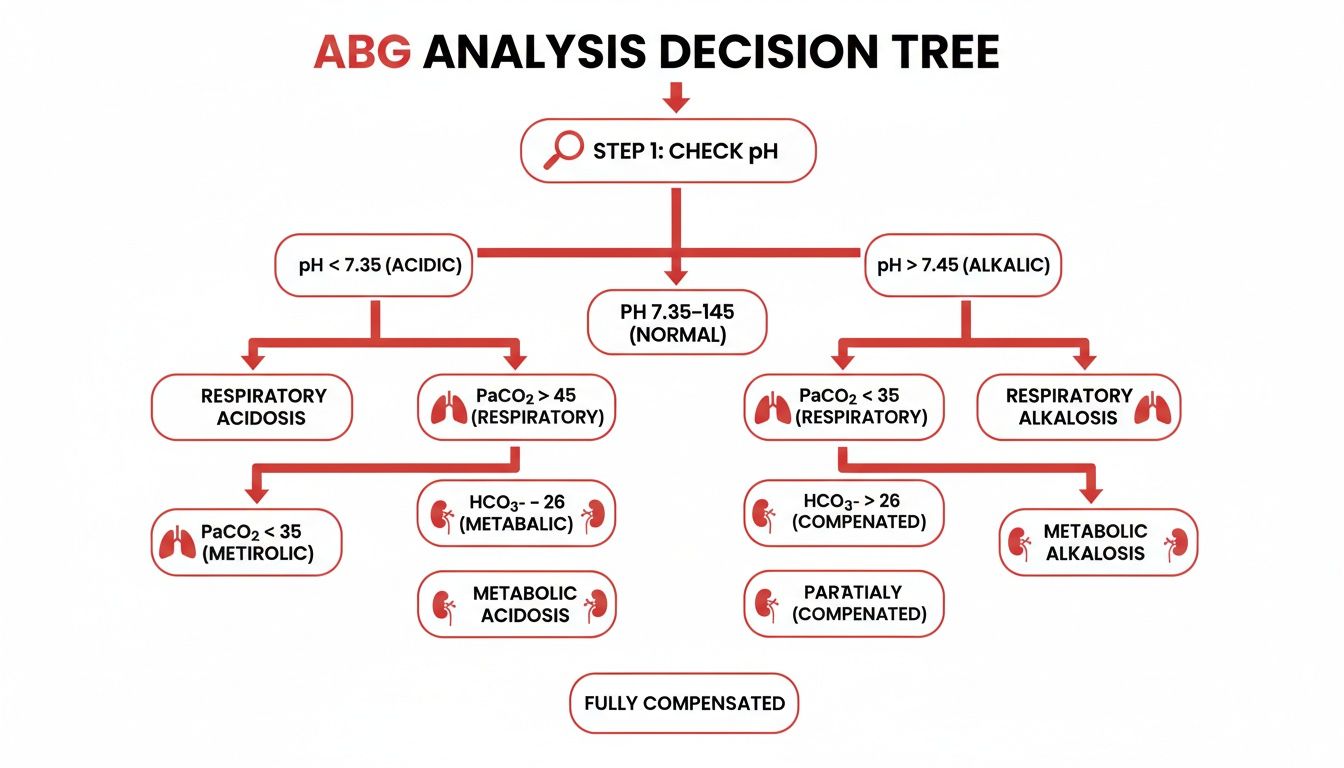

This decision tree gives you a great visual for those first few steps, starting with the pH and branching out to PaCO2 or HCO3- to nail down the primary disorder.

As the flowchart shows, checking the pH isn't just the first step—it's the non-negotiable anchor for your entire analysis.

Know Your Normal Values Cold

You can't spot the abnormal if you haven't mastered the normal. With arterial blood gas analysis performed in roughly 95% of ICU admissions, it's a true cornerstone of critical care. Committing the normal ranges to memory is non-negotiable.

Here is a quick-reference table with the critical values you'll need to have memorized for accurate interpretation on exams and in clinical practice.

Essential ABG Normal Values for Board Exams

| Parameter | Normal Range | Critical Low | Critical High |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.35–7.45 | < 7.20 | > 7.60 |

| PaCO2 | 35–45 mmHg | < 30 mmHg | > 50 mmHg |

| HCO3- | 22–26 mEq/L | < 18 mEq/L | > 30 mEq/L |

| PaO2 | 80–100 mmHg | < 60 mmHg | N/A |

These numbers are absolutely fundamental for your board examinations. They show up constantly on USMLE Steps 1, 2, and 3, as well as the COMLEX series. Having these values locked in your brain allows you to move quickly and confidently through any ABG problem that comes your way.

Mastering the Four Primary Acid-Base Disorders

Once you've got a solid system down, you can go beyond just naming a disturbance and start to really understand what's happening to your patient. The four primary acid-base disorders are the foundation for every ABG interpretation, from the textbook cases to the most confusing mixed pictures. Nailing their classic presentations is absolutely essential.

Think of each disorder as its own clinical story. Your job is to spot the main characters—pH, PaCO2, and HCO3−—and figure out how they're interacting to create the plot.

Respiratory Acidosis When Ventilation Falters

Respiratory acidosis is what happens when the lungs can't clear CO2 effectively, a state we call hypoventilation. As that CO2 piles up in the blood, it drives the pH down, making things acidic. The classic lab finding you'll see is an elevated PaCO2 (>45 mmHg) with a matching low pH (<7.35).

Picture a patient in the middle of a bad COPD exacerbation. Their airways are obstructed, trapping air and wrecking gas exchange. Their CO2 is going to climb, and the ABG will scream respiratory acidosis.

Common culprits include:

- Central Nervous System Depression: Think opioids, sedatives, or a head injury knocking out the respiratory drive.

- Airway Obstruction: Classic examples are asthma, COPD, or aspirating a foreign body.

- Impaired Respiratory Muscles: Conditions like Guillain-Barré syndrome or myasthenia gravis can weaken the muscles needed to breathe.

Clinical Insight: A sleepy patient who is hard to rouse after getting a dose of morphine is a classic board exam setup for respiratory acidosis. The opioid suppressed their respiratory drive, causing them to retain CO2.

Respiratory Alkalosis Hyperventilation's Effect

The flip side is respiratory alkalosis, which occurs when a patient is breathing too fast or too deep (hyperventilation) and blowing off way too much CO2. This aggressive removal of acid pulls the PaCO2 down and makes the pH shoot up. On the ABG, you're looking for a low PaCO2 (<35 mmHg)** and a **high pH (>7.45).

The textbook example is a patient having a panic attack. Their rapid, shallow breathing expels CO2 faster than their body can make it, pushing them into an alkalemic state.

Other common triggers are:

- Hypoxia: Low oxygen from something like a pulmonary embolism or being at high altitude tells the brain to ramp up the respiratory rate.

- Anxiety and Pain: Both are powerful stimulants for the respiratory center.

- Sepsis: Early on in sepsis, the body's inflammatory response can trigger hyperventilation.

Metabolic Acidosis An Excess of Acid or Loss of Base

Metabolic acidosis is a bit trickier. It’s defined by a primary drop in HCO3− (<22 mEq/L), which drags the pH down with it. This can happen in two main ways: either the body is gaining too much acid (like lactic acid in shock) or it's losing too much base (like from severe diarrhea).

This is where the anion gap becomes your best friend. Calculating it is a critical diagnostic step that helps you cut down the massive list of potential causes. For a deeper look at this key calculation, check out our guide on how to calculate the anion gap. A high anion gap metabolic acidosis (HAGMA) is often caused by the conditions remembered by the mnemonic MUDPILES.

Think of a patient in diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). Their body is churning out huge amounts of ketoacids, which chew up bicarbonate and send the pH plummeting.

Metabolic Alkalosis A Loss of Acid or Gain of Base

Finally, we have metabolic alkalosis, which is characterized by a primary increase in HCO3− (>26 mEq/L) that pushes the pH up. This disturbance usually pops up when the body either loses acid or gains way too much bicarbonate.

A common clinical scenario is a patient who can't stop vomiting. They're losing massive amounts of hydrochloric acid from their stomach, leaving a relative excess of bicarbonate in the blood and causing the pH to rise.

Other key causes to have on your radar:

- Diuretic Use: Loop and thiazide diuretics can cause significant losses of hydrogen ions.

- Contraction Alkalosis: When a patient gets severely dehydrated, the existing bicarbonate gets concentrated in a smaller blood volume.

- Excess Alkali Ingestion: Overdoing it with antacids is a less common but classic cause.

Getting these four fundamental patterns down cold is the key to successfully tackling any ABG. They are the bedrock upon which you'll build all the more advanced concepts, like compensation and mixed disorders.

Understanding Compensation and What It Tells You

Figuring out the primary disorder is a huge first step, but it's really only half the story. The next question you absolutely have to ask is: how is the body responding?

This response is called compensation, and it's the body's powerful, built-in mechanism to drag the pH back toward that normal range. Knowing whether this process is happening correctly is what separates a basic ABG read from a truly expert one.

The Lungs vs. The Kidneys

The body has two main players for balancing pH: the lungs and the kidneys. The lungs are the rapid responders, able to change pH within minutes just by adjusting breathing rate to blow off or hold onto CO2.

The kidneys, on the other hand, are the slow and steady workhorses. They take hours, sometimes even days, to fully adjust bicarbonate levels and make a lasting impact.

This timing difference is a critical clinical pearl. If a patient has a primary metabolic problem, their lungs will try to compensate almost immediately. But if the problem is respiratory, the kidneys need some serious time to mount a significant defense.

Is the Compensation Appropriate?

Just spotting compensation isn't enough. You have to figure out if the response is adequate. This is where a few high-yield formulas become your best friends, especially on exams.

These formulas let you calculate the expected compensatory response and then compare it to what you see on the patient's actual ABG. If there's a mismatch, it’s a massive clue that there's a second, or even third, acid-base disorder lurking beneath the surface.

Medical education research consistently shows that using a systematic approach, including calculating expected compensation, leads to much better learning outcomes. In fact, medical students who master these rules often score 25-30% higher on related board exam questions than students who just try to recognize patterns. You can dig into this research on effective ABG interpretation learning strategies for more details.

Let's break down the formulas you need to have locked in.

Calculating Respiratory Compensation in Metabolic Acidosis

When the body is in a metabolic acidosis, the lungs' job is to hyperventilate to blow off CO2 and nudge the pH back up. The most famous formula to check if they're doing their job properly is Winter's formula.

Winter's Formula: Expected PaCO2 = (1.5 x HCO3−) + 8 ± 2

Let's run through a quick example. A patient with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) has an HCO3- of 10 mEq/L.

- Calculate the expected PaCO2: (1.5 x 10) + 8 = 23 mmHg.

- This gives us an expected range of 21-25 mmHg (because of the ± 2).

If this patient's actual PaCO2 is 24 mmHg, their respiratory compensation is spot on. Perfect. But what if their PaCO2 was 35 mmHg? That's way higher than expected. This tells you they have their DKA plus a superimposed respiratory acidosis, probably because they are fatiguing and can't maintain the work of breathing.

Assessing Compensation in Respiratory Disorders

For respiratory problems, the body's metabolic compensation (via the kidneys) is all about time. We have very different expectations for an acute problem versus a chronic one.

- Acute Respiratory Acidosis: For every 10 mmHg increase in PaCO2 above 40, the HCO3- should increase by 1 mEq/L.

- Chronic Respiratory Acidosis: For every 10 mmHg increase in PaCO2 above 40, the HCO3- should increase by 3-4 mEq/L.

Let’s imagine a patient with a PaCO2 of 60 mmHg. That's 20 mmHg above the normal of 40.

- In an acute setting (like a heroin overdose), we'd expect the HCO3- to rise by 2 (1 for each 10-point rise), making the expected HCO3- around 26 mEq/L.

- In a chronic setting (like a stable COPD patient), we'd expect the HCO3- to rise by 6-8, putting the expected HCO3- in the 30-32 mEq/L range.

This distinction is everything. If your chronic COPD patient with a PaCO2 of 60 only has an HCO3- of 26, their renal compensation is falling short. This points to a coexisting metabolic acidosis that needs to be investigated.

Mastering these compensation rules isn't just about passing exams—it's about building a deep physiological understanding of how to interpret blood gases in complex, real-world clinical situations.

Uncovering Mixed Disorders with Advanced Analysis

Once you've nailed primary disorders and their expected compensations, you're ready to tackle the really tough stuff: mixed acid-base disorders. These are the complex clinical pictures where two or more primary disturbances are happening at once. Board examiners absolutely love these cases because they separate the students who just memorize from those who truly understand.

Think about a patient with sepsis who develops lactic acidosis but is also vomiting, which causes a metabolic alkalosis. Their ABG won't look like a simple, clean textbook example. Your job is to pick apart the numbers and reveal the multiple processes going on under the surface. This requires a few more tools in your diagnostic toolkit.

Calculate the Anion Gap Every Time

In any case of metabolic acidosis, your very first move should always be to calculate the anion gap (AG). This one calculation is the key that unlocks the differential diagnosis, splitting the possibilities neatly into two distinct buckets.

The formula is a classic:

Anion Gap = Na+ – (Cl– + HCO3–)

A normal anion gap usually falls between 8-12 mEq/L. An AG higher than this signals a high anion gap metabolic acidosis (HAGMA), which tells you that an unmeasured acid has been added to the system. This is where a good mnemonic becomes your best friend.

Pro Tip: Don't just calculate the anion gap when you see an obvious metabolic acidosis. Get in the habit of doing it on every set of electrolytes you see. Sometimes, a normal pH and bicarb can hide a mixed HAGMA and metabolic alkalosis, and that elevated gap will be your only clue that something is wrong.

Use MUDPILES for Your Differential

Once you've spotted a HAGMA, the next step is figuring out the cause. The MUDPILES mnemonic is a time-tested way to rapidly run through the most common culprits, which is critical when you're under pressure to build a strong list of potential diagnoses. When you are building a differential diagnosis, a structured approach like this is pure gold.

Here’s a breakdown of the high-yield causes you absolutely need to have memorized for your exams.

High-Yield Causes of Anion Gap Metabolic Acidosis (MUDPILES)

| Mnemonic Letter | Condition | Clinical Pearl |

|---|---|---|

| M | Methanol | Look for visual disturbances or the classic "snowstorm" vision. |

| U | Uremia (ESRD) | Suspect this in any patient with a known history of chronic kidney disease. |

| D | Diabetic Ketoacidosis | Often presents with hyperglycemia and deep, rapid Kussmaul respirations. |

| P | Propylene Glycol | This is a component of certain IV medications, like continuous lorazepam infusions. |

| I | Isoniazid, Iron | Consider in cases of overdose or specific medication histories. |

| L | Lactic Acidosis | The most common cause, usually from shock, sepsis, or severe tissue hypoxia. |

| E | Ethylene Glycol | Found in antifreeze; causes acute kidney injury and calcium oxalate crystals in the urine. |

| S | Salicylates (Aspirin) | A classic overdose presents with tinnitus and a mixed respiratory alkalosis. |

This mnemonic isn't just a list to memorize; it's a practical clinical tool that should prompt you to ask the right questions about a patient's history, medications, and presentation.

Decode Complexity with the Delta-Delta Ratio

So what happens when a patient has a HAGMA, but the numbers still don't seem to quite add up? This is where the delta-delta ratio (also called the delta gap) becomes an incredibly powerful tool. It helps you see if another metabolic disorder is lurking behind the anion gap acidosis.

The delta-delta ratio essentially compares the change in the anion gap to the change in bicarbonate.

Delta Ratio = (Measured AG – Normal AG) / (Normal HCO3– – Measured HCO3–)

Here’s how to make sense of the results:

- A ratio between 1.0 and 2.0 points to a pure high anion gap metabolic acidosis. The drop in bicarbonate is roughly equal to the rise in the anion gap, which is exactly what you'd expect.

- A ratio < 1.0 tells you that the bicarbonate has fallen more than the anion gap has risen. This means there's a coexisting non-anion gap metabolic acidosis (NAGMA). The classic example is a DKA patient who also has severe diarrhea.

- A ratio > 2.0 means the bicarbonate has fallen less than you'd expect for the rise in the anion gap. This is a huge clue that a concurrent metabolic alkalosis is present. Picture that same DKA patient, but this time they've been vomiting profusely.

By applying these advanced calculations, you can move beyond a surface-level interpretation of the ABG. You'll be able to confidently identify complex mixed disorders, explain the underlying pathophysiology, and develop a much more precise treatment plan. This is the level of analysis that separates the top performers on the wards and on exam day.

Putting Your ABG Interpretation Skills to the Test

Alright, the theory and formulas are locked in. But the real learning—the kind that sticks—happens when you apply that knowledge to actual clinical scenarios. This is where your systematic approach, compensation rules, and those advanced calculations all come together to solve a real patient's problem.

Let's work through a few board-style cases to sharpen your skills and build the confidence you need for both exams and the wards. We'll walk through each one step-by-step, showing you the thought process that gets you to the right diagnosis.

Case 1: A Post-Operative Patient with Slow Breathing

You're called to the PACU to see a 68-year-old male recovering from a partial colectomy. He received a fair amount of intraoperative opioids and is now difficult to arouse. His respiratory rate is only 8 breaths per minute.

His labs pop up:

- pH: 7.28

- PaCO2: 58 mmHg

- HCO3−: 25 mEq/L

- Na+: 140 mEq/L

- Cl−: 102 mEq/L

First, let's run our system. The pH is 7.28, which is clearly acidemia. What's driving it? The PaCO2 is high at 58 mmHg, which definitely explains the acidosis. Meanwhile, the HCO3− is normal at 25 mEq/L.

Thinking back to our ROME mnemonic, the pH is down and the PaCO2 is up—they're moving in opposite directions. This confirms a respiratory acidosis.

So, is there any compensation? Since the bicarbonate is smack in the normal range, the answer is no. This is a clean, uncompensated respiratory acidosis, and the clinical context of opioid-induced hypoventilation fits perfectly.

Case 2: A Young Woman with Sepsis

A 22-year-old woman with a history of type 1 diabetes is brought to the ED with fever, hypotension, and altered mental status. You notice she's breathing rapidly and deeply (Kussmaul breathing).

Her labs:

- pH: 7.15

- PaCO2: 22 mmHg

- HCO3−: 8 mEq/L

- Na+: 135 mEq/L

- Cl−: 100 mEq/L

- Glucose: 450 mg/dL

The pH of 7.15 points to a severe acidemia. The PaCO2 is low at 22 mmHg, which would cause an alkalosis, so that can't be the primary problem. But the HCO3− is very low at 8 mEq/L, which absolutely explains the acidemia. This is a metabolic acidosis.

Diagnostic Step: Any time you see a metabolic acidosis, your very next thought must be to calculate the anion gap.

Anion Gap = Na+ – (Cl− + HCO3−)

AG = 135 – (100 + 8) = 27 mEq/L

An anion gap of 27 is significantly elevated (normal is 8-12 mEq/L), making this a high anion gap metabolic acidosis (HAGMA). The clinical picture of a diabetic patient with sky-high blood sugar is a classic setup for diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA).

But we're not done. Is her respiratory system compensating appropriately? For this, we need Winter’s formula:

Expected PaCO2 = (1.5 x HCO3−) + 8 ± 2

Expected PaCO2 = (1.5 x 8) + 8 = 20 mmHg

The expected range for her PaCO2 is 18-22 mmHg. Her actual PaCO2 is 22 mmHg, falling perfectly within this range. This tells us her respiratory compensation is adequate. The final diagnosis: HAGMA due to DKA with appropriate respiratory compensation.

Case 3: A Complex ICU Patient

A 75-year-old man with a known history of COPD and chronic kidney disease is in the ICU for sepsis. He's intubated and on a ventilator. A few days into his stay, he develops severe diarrhea from a C. difficile infection.

His latest labs show:

- pH: 7.25

- PaCO2: 60 mmHg

- HCO3−: 18 mEq/L

- Na+: 138 mEq/L

- Cl−: 110 mEq/L

This one is a bit trickier. The pH is 7.25, so we have an acidemia. But look closer—both the PaCO2 is high (60 mmHg) and the HCO3− is low (18 mEq/L). Each of these abnormalities would cause an acidosis on its own. This is the classic signature of a mixed disorder. This patient has both a respiratory acidosis (from his underlying COPD) and a metabolic acidosis.

Let's dig deeper into the metabolic piece by calculating the anion gap.

AG = 138 – (110 + 18) = 10 mEq/L

The anion gap is normal. This means he has a non-anion gap metabolic acidosis (NAGMA). This makes perfect clinical sense, given his severe diarrhea and the associated loss of bicarbonate.

His final, complete diagnosis is a mixed respiratory acidosis and non-anion gap metabolic acidosis.

Working through complex cases like these is the best way to train your diagnostic muscles. As you encounter more of them, it becomes essential to continually improve your critical thinking skills so you can seamlessly connect the lab data to the patient in front of you.

Common Questions on ABG Interpretation

Even with a solid system, some parts of ABG interpretation just feel sticky. These are the classic stumbling blocks that trip people up on exams and create confusion on the wards. Let’s clear up a few of the most common questions to make sure your understanding is rock-solid.

One of the biggest hurdles is getting the hang of acute versus chronic respiratory compensation. Just remember: the kidneys are slow. In a sudden respiratory problem, like an acute asthma attack, the kidneys haven't had time to react and adjust bicarbonate. But in a chronic issue, like long-standing COPD, they've had days or weeks to get their act together, leading to a much higher bicarbonate to balance out the retained CO2.

Why Is My Patient’s pH Normal with Abnormal Values?

Seeing a pH of 7.40 alongside a high PaCO2 and a high HCO3- can definitely make you pause. This isn't a normal ABG. It’s actually a sign of a fully compensated disorder. The body has worked so hard to fix the primary problem that it managed to drag the pH right back into the normal range.

So how do you figure out what started it all? The key is to see which side of 7.40 the pH is leaning toward.

- A pH of 7.36 is on the acidic side of normal, pointing to a primary acidosis.

- A pH of 7.44 is on the alkaline side, suggesting a primary alkalosis.

Exam Pitfall: A classic mistake is to see a normal-range pH and call the whole ABG "normal." That's a guaranteed wrong answer on an exam. The correct description will always name the underlying issue, like "fully compensated respiratory acidosis."

When to Suspect a Mixed Disorder

Sometimes, it’s not just one thing going wrong. Beyond the obvious cases where PaCO2 and HCO3- are both moving in a way that explains the pH, there are subtle clues that point to a mixed acid-base disorder.

The biggest red flag is inappropriate compensation. If you do the math to calculate the expected compensation and the patient's actual value is way off, you can bet there's a second disorder hiding in there.

For instance, think about a patient with a nasty metabolic acidosis. Their lungs should be working like crazy to blow off CO2, so you'd expect a very low PaCO2. If their PaCO2 is just sitting in the normal range, that's not good—it’s a sign of a coexisting respiratory failure. They aren't compensating like they should be, meaning you're looking at a mixed metabolic and respiratory acidosis. This is a critical find because it signals the patient is tiring out and might need ventilatory support. Learning to spot these compensation failures is a huge step in mastering ABGs in complex patients.

Navigating the complexities of ABG interpretation is a crucial skill for exam success and clinical excellence. At Ace Med Boards, we specialize in breaking down these high-yield topics with personalized, one-on-one tutoring for the USMLE, COMLEX, and Shelf exams. Get started with a free consultation today!