Intention-to-treat analysis is a core principle in clinical trials that often trips students up on board exams. The basic idea is that all participants are analyzed in the group they were originally assigned to, no matter what happens later.

It doesn't matter if they quit the study, didn't take the medication, or even switched over to the other group's treatment. This is the "once randomized, always analyzed" philosophy, and it's critical for preserving the integrity of the trial.

Understanding Intention to Treat Analysis for Your Boards

Let's break down what intention-to-treat analysis really means with a simple analogy.

Imagine you're a soccer coach testing a new, grueling training regimen you believe will boost player speed. At the start of the season, you randomly assign your 100 players into two groups: 50 get the new regimen, and 50 stick with the standard training.

But reality hits. As the season goes on, some players in the new regimen group get minor injuries. Others find it too tough and stop showing up consistently. By the end of the season, only 35 of the original 50 are still following your new plan perfectly.

A biased analysis might be tempted to only compare the 35 "perfectly compliant" players to the control group. This approach, however, would almost certainly make the new regimen look far more effective than it truly is, because you'd be ignoring all the players for whom it didn't work out.

Preserving Real-World Conditions

This is where intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis comes in. ITT forces you, the coach, to analyze the results of all 50 players originally assigned to the new regimen—even the ones who dropped out or couldn't keep up.

Why? Because ITT answers a much more practical and realistic question: "What is the overall effect of assigning this training plan to my team?" This approach mirrors the messy reality of clinical practice, where patients aren't always perfect with their treatment plans.

This is the absolute key concept you need to lock down for your exams. ITT isn't about measuring a treatment's effect under ideal, perfect-world conditions; it’s about gauging its effectiveness in the real world, complete with all its imperfections like non-adherence and dropouts.

The foundational rule of ITT is simple yet powerful: Analyze participants based on the group they were intended to be in, not the treatment they actually received. This maintains the benefits of randomization and provides a more conservative, realistic estimate of a treatment's effect.

To help you nail this concept for exam day, we've broken down the core principles of ITT into a quick-glance table. For more tips on making these ideas stick, check out our guide on effective study methods for memorization.

Core Principles of Intention to Treat Analysis

| Principle | What It Means for a Clinical Trial | Why It Matters for Exam Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Inclusivity | All randomized patients are included in the final analysis, regardless of adherence or dropout. | This is the primary definition. Questions will test if you know to include everyone assigned to a group. |

| Preservation of Randomization | It maintains the initial balance between the treatment and control groups, preventing selection bias. | ITT is considered the 'gold standard' because it avoids the bias that comes from selectively excluding patients. |

| Real-World Effectiveness | The results reflect how a treatment will perform in a typical patient population with imperfect compliance. | This distinguishes ITT from other analyses (like per-protocol) that measure efficacy in only ideal, compliant settings. |

Remembering these three pillars—inclusivity, preserving randomization, and real-world effectiveness—will give you a solid framework for tackling any ITT-related question that comes your way.

Why ITT Is Essential for Preserving Randomization

The single most important reason intention-to-treat analysis is the gold standard for clinical trials comes down to one core principle: it preserves the integrity of randomization. When a study begins, researchers go to great lengths to randomize participants, creating treatment and control groups that are, on average, statistically identical.

This initial balance is the bedrock of a trustworthy trial. It ensures that the only significant difference between the groups is the intervention we’re testing. But this perfect balance is incredibly fragile and can be easily shattered by the messy reality of human behavior.

The Problem with Perfect Patients

Let's walk through a classic scenario. Imagine a study testing a new heart failure medication. The researchers randomize 1,000 patients into two groups: 500 get the new drug, and 500 get a placebo. The goal is to see if the drug can reduce hospitalizations over the next two years.

Over that time, life happens.

- Some patients in the drug group will forget to take their pills.

- Others might stop the medication because of side effects.

- A few might just drop out of the study entirely for personal reasons.

Now, what if the researchers decided to only analyze the "perfect" patients—the ones who took the new drug exactly as prescribed? This would completely destroy the original randomization. The group of compliant patients is almost certainly different from those who dropped out. They might be younger, healthier, or just more motivated, creating a powerful selection bias.

Comparing this "best-case" group to the original control group would rig the game, making the drug look far more effective than it truly is in the real world.

An analysis that kicks out non-compliant participants is no longer comparing randomized groups. It becomes a skewed comparison between a highly motivated, compliant group and the original control group. That’s not a fair fight.

This is precisely the kind of trap board exam questions love to set. They'll present data showing a treatment is a miracle cure but then casually mention that "only patients who completed the full therapy were included." That’s a massive red flag signaling a biased, unreliable analysis. Understanding how these treatment effects are quantified is also key; you might want to check out our guide on the Number Needed to Treat (NNT).

How ITT Provides a Realistic Answer

Intention-to-treat analysis avoids this bias by following one simple, unbreakable rule: analyze everyone in the group they were originally assigned to. It doesn't matter if they took the drug, stopped it, or never even started. "Once randomized, always analyzed."

This approach mirrors the messy reality of clinical practice, where non-compliance is just part of the job. In fact, nonadherence rates in chronic disease studies can be anywhere from 20-50%, with dropout rates often hitting 15-25%.

ITT embraces this messiness to give us a more conservative and realistic estimate of the treatment's effect in the general population. By keeping the original groups intact, ITT gives an honest answer to the most practical clinical question we can ask: "What happens when we prescribe this drug?"

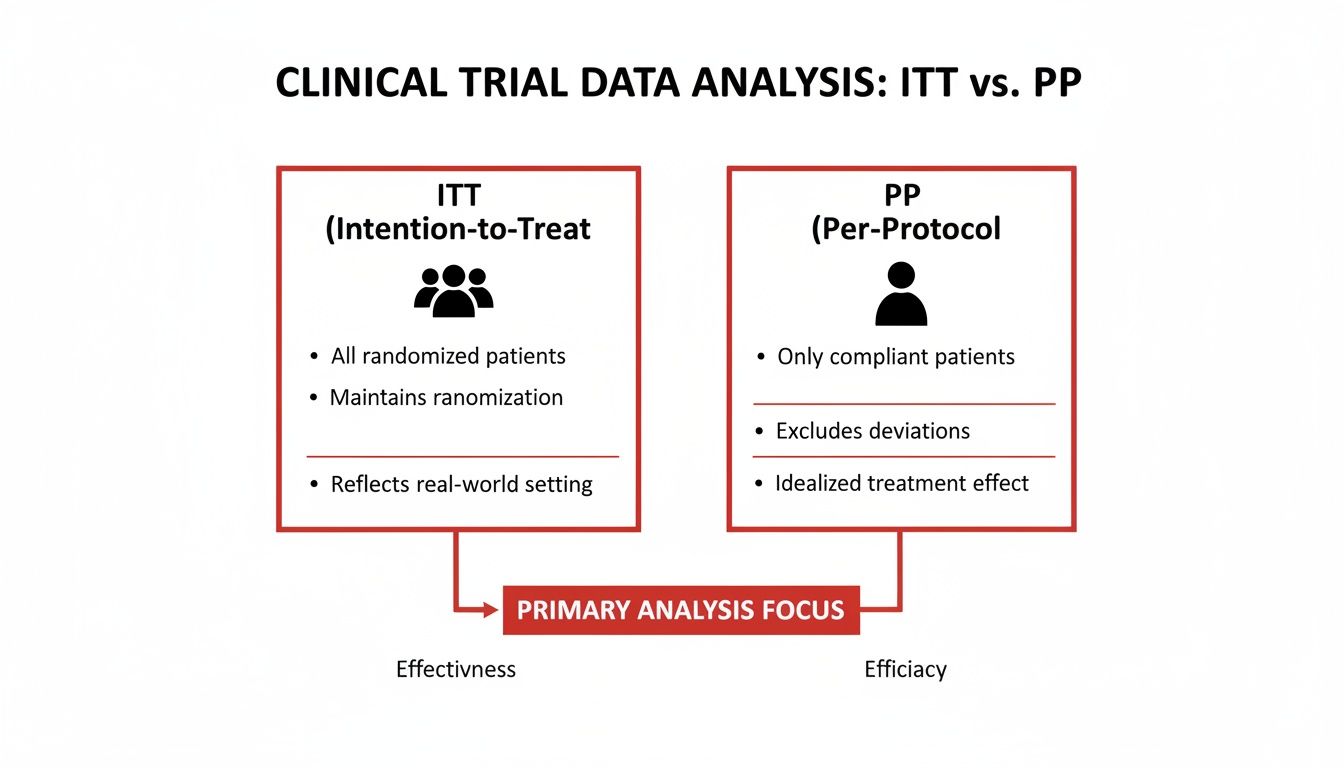

ITT Versus Per-Protocol Analysis For The USMLE

When you're grinding through USMLE questions, knowing the difference between Intention-to-Treat (ITT) and Per-Protocol (PP) analysis isn't just a good idea—it's non-negotiable. Get this wrong, and you're leaving easy points on the table.

Think of it this way: ITT is like judging a new training plan based on everyone who signed up for the gym, including the people who only showed up once. PP is like judging that same plan based only on the super-motivated people who followed it to the letter. USMLE questions love to test if you can spot which result reflects the messy reality of clinical practice versus an idealized, lab-perfect scenario.

Effectiveness vs. Efficacy: What Are We Actually Measuring?

ITT analysis is all about effectiveness. It tackles the practical, real-world question: "If I prescribe this drug, what is likely to happen in my patient population?" It keeps every single person who was randomized in the analysis, even if they stopped taking the drug, crossed over to the other group, or dropped out entirely. This gives you a conservative but realistic picture.

Per-Protocol (PP) analysis, on the other hand, measures efficacy. It answers a more theoretical question: "Under perfect conditions, what is the maximum biological benefit of this treatment?" To do this, it only includes the "perfect patients"—the ones who did everything right and stuck to the plan flawlessly.

The Trade-Off: Purity vs. Reality

It’s tempting to think the PP analysis is better because it shows a treatment’s pure effect, right? Not so fast. The problem is that kicking people out of the analysis introduces a massive risk of bias.

By excluding patients who couldn't tolerate the treatment (maybe due to nasty side effects) or just weren't compliant, you break the magic of randomization. The group that’s left is often inherently healthier or more motivated, which can make the treatment look way more impressive than it actually is.

ITT saves the day by keeping everyone in their original assigned groups. This preserves the beautiful balance you get from randomization and makes the conclusions something you can actually apply to the patients you'll see in the clinic.

USMLE Pro-Tip: If a question forces you to choose the most valid interpretation of a trial's results, the conclusion based on intention-to-treat analysis is almost always the right answer. It’s grounded in unbiased, real-world data, not a cherry-picked, idealized scenario.

A Head-to-Head Comparison

To really nail this down, let’s put these two methods side-by-side. As you read this table, think about how a clinical vignette could use subtle wording to nudge you toward one analysis or the other.

Intention-to-Treat (ITT) vs. Per-Protocol (PP) Analysis

| Feature | Intention-to-Treat (ITT) Analysis | Per-Protocol (PP) Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Who Is Analyzed? | All randomized patients, no matter what they did after being assigned a group. | Only patients who completed the study and followed the protocol perfectly. |

| Primary Question | What is the treatment's effectiveness in a real-world setting? | What is the treatment's maximum efficacy under ideal conditions? |

| Risk of Bias | Low. It preserves randomization and avoids the kind of selection bias that skews results. | High. It creates selection bias by kicking out certain participants after randomization. |

| Treatment Effect | Tends to be more conservative and realistic (the effect might seem "diluted"). | Tends to overestimate the treatment's benefit, sometimes dramatically. |

| When to Trust It | Considered the gold standard for most clinical questions, especially in superiority trials. | Useful for understanding a drug's potential, but its results must be interpreted with extreme caution. |

The gap between what these two analyses show can be huge. ITT gives you a grounded, conservative effect. PP analysis, by focusing on a smaller, hyper-compliant subset (often just 60-85% of the original group), can inflate the apparent efficacy and introduce bias by as much as 25%.

For instance, a major meta-analysis of antidepressants found that the ITT analysis showed a modest benefit. The PP analysis, however, overestimated the effect by nearly 30%, which fueled claims that were later challenged by more robust data. For a deeper dive into these concepts, you can explore the data on Rethinking Clinical Trials.

Getting a handle on these differences is key for acing biostats questions and for correctly interpreting any clinical trial data you see on your exams. While you're at it, you might want to brush up on other core concepts by checking out our guide on what is sensitivity and specificity.

How ITT Became the Gold Standard in Research

Intention-to-treat analysis didn't just appear overnight; its journey to becoming the undisputed gold standard in clinical research was a direct response to a major problem. Before ITT was widely adopted, many studies were plagued by a critical flaw: researchers would often exclude patients who didn't follow the trial's rules perfectly.

This practice created a huge bias, leading to overly optimistic—and sometimes dangerously misleading—conclusions about how well a new treatment actually worked. The results only reflected the "perfect" patients, not the messy reality of clinical practice.

Researchers knew they needed a more honest and rigorous method. The answer began to take shape in the 1960s with the formalization of ITT, a principle designed to protect the integrity of randomization from the moment a patient enrolls to the final analysis. By the 1990s, its importance was undeniable.

Mandated by Leading Authorities

The real shift happened when major regulatory bodies and guideline creators threw their weight behind ITT. The CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) statement, first published in 1996, essentially mandated ITT for any trial to be considered transparent and credible.

Around the same time, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) began requiring ITT analysis for new drug approvals. They needed to ensure their decisions were based on the most robust, real-world evidence possible. You can get more of the historical context in this detailed overview of clinical trial analysis.

This diagram gives a great visual breakdown of how ITT's inclusive approach stacks up against the more selective per-protocol analysis.

As you can see, ITT keeps the original, diverse patient groups intact. In contrast, per-protocol analysis narrows its focus, looking only at the most compliant individuals, which can skew the results.

By enforcing the rule to "analyze as you randomize," ITT ensures that a study's conclusion reflects what happens when a treatment is prescribed in the real world—not just in a perfect, controlled bubble. This principle is the bedrock of evidence-based medicine.

This commitment to real-world data is why getting a handle on ITT is so critical, not just for acing your exams but for your entire future in medicine. And for those looking to get involved in this kind of work early on, our guide on building a competitive residency application through medical student research offers some great starting points.

Navigating a Board-Style ITT Question

Knowing the theory is one thing, but applying it under the pressure of a high-stakes exam is a completely different ballgame. Let's walk through a classic clinical vignette to see how these concepts show up on exam day.

Getting the logic down cold here is a huge part of your prep. If you want to sharpen your overall approach, our guide on how to improve test-taking skills has some fantastic strategies.

The Clinical Vignette

A multicenter, randomized controlled trial is conducted to evaluate a new oral anticoagulant, "Drug X," for stroke prevention in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. A total of 2,000 patients are randomized. 1,000 patients are assigned to receive Drug X, and 1,000 are assigned to receive warfarin.

Over the three-year study period, 150 patients in the Drug X group discontinue the medication due to side effects, and 50 are lost to follow-up. In the warfarin group, 100 patients stop taking their medication, and 75 are lost to follow-up. The primary outcome is the incidence of ischemic stroke.

An analysis is performed based on the groups to which patients were originally assigned. The results show that the stroke rate in the Drug X group was 3.5% and 5.0% in the warfarin group (p=0.04). A separate analysis including only patients who adhered to their assigned treatment for the full three years found a stroke rate of 2.0% for Drug X and 5.2% for warfarin (p<0.01).

Which of the following is the most appropriate conclusion from this study?

Breaking Down the Question

First things first, you have to dissect the question stem. What’s the study design and what analyses are they showing you? The moment you read "randomized controlled trial," your brain should immediately start thinking about randomization, bias, and the best way to analyze the results.

Then, the vignette serves up two different sets of results. This is a classic board exam trick designed to test if you truly understand the difference between ITT and per-protocol analysis.

The money phrase is right here: "An analysis is performed based on the groups to which patients were originally assigned." That's the textbook definition of an intention-to-treat analysis. It’s your signal that this is the most trustworthy result.

The second result, which only includes "patients who adhered to their assigned treatment," is a per-protocol analysis. See how the p-value is way lower (<0.01)? And how Drug X looks like a superstar drug? That’s the distractor. It’s the shiny, exciting result designed to tempt you away from the right answer.

Selecting the Correct Interpretation

Your job is to pick the most scientifically solid conclusion. The ITT result (3.5% vs. 5.0%, p=0.04) is the one that honors the original randomization. It gives you a real-world picture of what happens when you prescribe Drug X, acknowledging that in reality, some patients are going to stop taking it for one reason or another.

The per-protocol result (2.0% vs. 5.2%, p<0.01) is fundamentally biased. It kicks out 200 patients from the Drug X group and 175 from the warfarin group. Who knows why they really dropped out? By excluding them, you've broken the randomization, and the result probably makes Drug X look much better than it actually is.

So, the most appropriate conclusion is that Drug X shows a modest benefit over warfarin for preventing strokes in this population, as shown by the intention-to-treat analysis. Any answer choice that hypes up the per-protocol finding is the wrong one.

As you continue to build your clinical knowledge, exploring additional medical training resources can really help solidify these concepts for exam day and beyond.

Common Questions About Intention to Treat Analysis

Even with a solid grasp of the basics, a few tricky points about intention-to-treat analysis can still trip you up. Let's walk through the most common questions that pop up for medical students, making sure you're ready for whatever the exams throw your way.

If ITT Is So Realistic, Why Do Researchers Bother Reporting Per-Protocol Results?

This is a great question. Researchers often report both because they’re trying to answer two fundamentally different questions about a new treatment.

Think of it like this:

- Intention-to-Treat (ITT): This answers the question, "How well does the strategy of prescribing this drug work in the real world?" It accounts for all the messy stuff—patients forgetting to take their meds, stopping because of side effects, or dropping out of the study. This tells us about a treatment's effectiveness.

- Per-Protocol (PP): This answers the question, "How well does this drug work under perfect conditions?" It only looks at the people who followed the instructions to a T. This tells us about a treatment’s maximum potential, or its efficacy.

By presenting both, researchers give clinicians a full picture. They can see the pragmatic, real-world benefit (ITT) right next to the drug's theoretical best-case-scenario power (PP).

Does ITT Analysis Always Make a New Treatment Look Less Effective?

Often, yes—but that's a feature, not a bug. ITT analysis tends to produce a more conservative or "diluted" treatment effect.

Why? Because it includes everyone, even the non-compliant patients who barely took the new drug and the people in the placebo group who secretly started taking the active drug. This mixing dilutes the final result, pulling it closer to the null hypothesis (no difference).

But this is exactly what makes it so valuable. It prevents the overly optimistic—and potentially misleading—results you’d get by only looking at the "perfect" patients.

An ITT analysis provides a more honest and pragmatic estimate of what you can expect when you prescribe this treatment to your own patients. For your exams, remember that ITT provides a realistic result, which isn't always the most impressive one.

This conservative estimate is exactly what we need to make safe and effective clinical decisions.

How Can I Spot an ITT Analysis in a USMLE Question?

When you’re staring at a clinical vignette on exam day, you need to know what to look for in the methods section. The most obvious clue is a direct statement like, "an intention-to-treat analysis was performed."

But they might be more subtle. Look for phrases that mean the same thing:

- "All randomized patients were included in the final analysis, regardless of adherence."

- "The analysis was based on the group to which patients were originally assigned."

On the flip side, be on high alert for the opposite. If you read that "only patients who completed the study were analyzed" or "non-compliant patients were excluded," that's a massive red flag. You're looking at a biased per-protocol analysis, and the question is likely testing your ability to spot that bias.

Feeling ready to conquer your boards? At Ace Med Boards, we provide personalized, one-on-one tutoring to help you master high-yield topics like biostatistics and crush your exams. Learn more about our tutoring services.