When a patient's kidneys are failing, every minute counts. How do clinicians quickly decide if it's a true emergency that demands immediate dialysis? The answer often lies in a simple but incredibly powerful mnemonic: AEIOU.

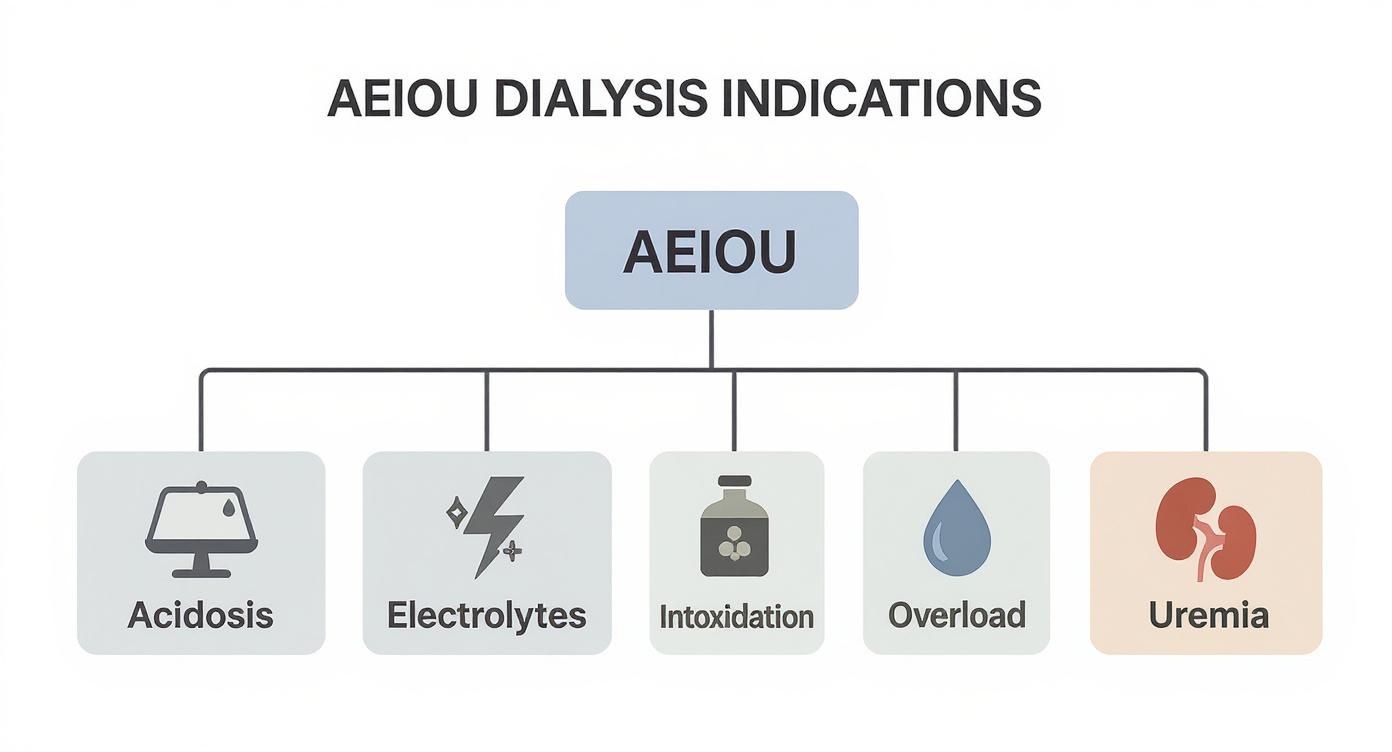

This framework breaks down the five life-threatening indications for urgent renal replacement therapy: Acidosis, Electrolytes, Intoxication, Overload, and Uremia. Think of it as a mental checklist that guides you through a high-stakes clinical decision.

The AEIOU Mnemonic: A Lifesaving Clinical Framework

In the chaos of an emergency department or ICU, memorable frameworks aren't just helpful—they're essential. The AEIOU mnemonic is a cornerstone of renal and internal medicine for this very reason. It cuts through the complexity of acute kidney injury (AKI) or end-stage renal disease (ESRD), allowing for rapid, structured assessment.

This simple tool ensures that even under pressure, no critical indication for dialysis gets missed.

As you can see, the framework neatly separates the five distinct but often interconnected emergencies, from metabolic chaos like acidosis to systemic poisoning like uremia.

Why This Framework Is More Important Than Ever

Grasping these indications isn't just an academic exercise; it's a critical clinical skill. The global burden of chronic kidney disease (CKD) is staggering, affecting an estimated 850 million people worldwide as of 2023—that's nearly 10% of the global population. This number continues to climb, driven by rising rates of diabetes and hypertension.

Mastering the AEIOU mnemonic is a must for any clinician. It’s a high-yield topic that shows up constantly on board exams and is a foundational piece of any solid internal medicine shelf review.

The AEIOU framework isn't just about hitting a specific lab value. It's about looking at the whole patient and asking the right question: "Is this condition life-threatening and failing to respond to medical management?" If the answer is yes, dialysis moves from an option to a necessity.

To give you a quick overview before we dive deep, here's a summary of what each letter in the AEIOU mnemonic stands for.

The AEIOU Mnemonic at a Glance

This table provides a high-level summary of the five core indications for urgent dialysis and the primary triggers that should put them on your radar.

| Mnemonic | Indication | Primary Clinical Trigger |

|---|---|---|

| A | Acidosis | Severe metabolic acidosis (e.g., pH <7.1) refractory to bicarbonate therapy. |

| E | Electrolytes | Severe hyperkalemia (e.g., K >6.5 mEq/L) with ECG changes. |

| I | Intoxication | Ingestion of a dialyzable toxin (e.g., methanol, ethylene glycol). |

| O | Overload (Fluid) | Refractory pulmonary edema despite aggressive diuretic use. |

| U | Uremia | Symptomatic uremia (e.g., encephalopathy, pericarditis). |

This table is just the starting point. In the sections that follow, we'll break down each of these indications, exploring the specific clinical signs and lab values that signal it's time to call nephrology for this life-saving procedure.

A for Acidosis: When pH Levels Reach a Tipping Point

Think of your body's internal chemistry like a finely balanced swimming pool. For everything to work right, the pH needs to stay in a very tight, slightly alkaline range. When kidneys fail, they can no longer filter acidic waste from the blood, and this delicate balance gets thrown into chaos. The result is a dangerous condition called metabolic acidosis.

This isn't some minor chemical imbalance; it's a full-blown crisis that messes with how your enzymes, cells, and organs function. As acid builds up, it can disrupt everything from breathing patterns to the way your heart contracts. This is a true medical emergency, and it's the "A" in our AEIOU mnemonic for a reason.

Identifying the Danger Zone for Acidosis

Now, we don't rush a patient to dialysis at the first sign of a pH shift. The body has some powerful buffering systems to fight back, and the first line of defense is often giving IV sodium bicarbonate to neutralize the acid. But there's a clear tipping point where those measures just can't keep up.

Dialysis becomes an urgent necessity when the acidosis is both severe and refractory—meaning it’s not getting better despite medical treatment. The red flags that scream "we need dialysis now" include:

- Severe Acidemia: A blood pH that drops below 7.1 is generally considered the critical threshold. At this point, normal cellular function is severely compromised.

- Refractory to Bicarbonate: You've given the patient plenty of bicarbonate therapy, but their pH just isn't budging.

- High Anion Gap: This lab value tells you there are unmeasured acids floating around in the blood, often from toxins (like methanol or ethylene glycol) or metabolic byproducts like lactic acid.

A classic clinical pearl here is that while the absolute pH number is a guide, the trend is just as critical. A pH that's rapidly falling, even if it's still technically above 7.1, signals a process spiraling out of control. That patient might need dialysis sooner rather than later.

How Dialysis Provides the Definitive Fix

When medical therapy fails, dialysis offers a powerful, two-pronged solution that nothing else can match. First, it directly corrects the pH. The dialysis machine uses a bicarbonate-rich fluid called dialysate to effectively wash the excess acid out of the blood.

But more importantly, dialysis tackles the root of the problem by removing the source of the acid itself. This is absolutely critical in cases of intoxication, where the acidosis is being fueled by a substance that can be filtered out by the dialysis machine.

Example Vignette

A patient is brought into the ER confused, with deep, rapid breathing. They might have ingested something, but no one is sure what. Their labs come back showing a profound metabolic acidosis with a pH of 7.0 and a massive anion gap. You give them multiple amps of bicarbonate, but the pH doesn't improve.

This is a textbook indication for urgent hemodialysis. The goal is twofold: correct the life-threatening acidemia immediately and remove whatever toxin is causing it. In this scenario, dialysis isn't just a supportive measure—it's the definitive treatment.

E for Electrolytes: Correcting Dangerous Electrical Imbalances

Think of your heart and nervous system as a highly sensitive electrical grid. This grid depends on a perfect balance of electrolytes to function, and potassium is one of the master regulators. When kidneys fail, they can no longer get rid of potassium, causing its level in the blood to surge—a dangerous state called hyperkalemia.

This is like sending a massive power surge through a delicate computer circuit. The excess potassium wrecks the normal electrical signals that make the heart beat. This instability can quickly lead to a complete and fatal shutdown: cardiac arrest. This is exactly why a severe electrolyte imbalance is one of the most urgent reasons to start dialysis.

Recognizing the Electrical Warning Signs

We don't just look at the raw potassium number on a lab report. We hunt for evidence of its toxic effects on the heart using an electrocardiogram (ECG). Severe hyperkalemia becomes an emergency call for dialysis when medical therapies aren't working or when we see clear signs of cardiac toxicity.

Key red flags that tell us an electrical crisis is imminent include:

- Critical Potassium Level: A serum potassium greater than 6.5 mEq/L is usually the trigger for urgent action. However, some patients can show dangerous signs at even lower levels.

- ECG Changes: This is the visual proof of the heart's instability. The classic progression starts with peaked T waves, moves to a widened QRS complex, and can ultimately devolve into a sine wave pattern—the last stop before cardiac arrest.

- Refractory to Medical Management: This means the patient has already received medications like insulin, glucose, and albuterol, but their potassium level stubbornly remains in the danger zone.

For a deeper dive into what these electrical changes look like, check out this great resource on understanding electrolyte imbalance and its ECG manifestations.

Why Dialysis Is the Definitive Solution

While emergency medications can offer a temporary fix, they don't actually remove any potassium from the body. Think of them as a quick patch—they temporarily shift the excess potassium out of the bloodstream and into the body's cells. This buys us precious time, but it does absolutely nothing to solve the root problem of total body potassium overload.

The crucial distinction is that medical therapies shift potassium, but only dialysis can physically remove it. When the heart is at risk, removal is the only definitive way to restore electrical stability and prevent a fatal arrhythmia.

Dialysis acts as an artificial kidney, filtering the blood against a special fluid called dialysate, which has a low potassium concentration. This concentration gradient efficiently pulls the excess potassium right out of the patient's blood. This directly lowers the serum level, allowing the heart's electrical system to reset to a safe, stable rhythm. It's the ultimate safety net when the body's own system has completely failed.

I for Intoxication: Filtering Poisons from the Bloodstream

Sometimes, the kidneys are overwhelmed not by internal waste but by an external assault. When a person ingests a toxic substance or overdoses on a medication, their natural filtration system can be completely outmatched. In these critical situations, dialysis shifts from a supportive role to a primary, life-saving intervention.

Think of dialysis here as an external, super-powered filter. It rapidly cleans the entire bloodstream, pulling out the harmful substance much faster than the body ever could on its own. This is the "I" in the AEIOU mnemonic, representing a direct and aggressive approach to treating severe poisonings.

Which Toxins Can Be Filtered Out?

Unfortunately, we can't just dialyze away every poison. For a substance to be effectively "dialyzable," it needs to have specific chemical properties. Understanding these is key to knowing when to make the urgent call to nephrology.

A dialyzable substance typically has:

- Low Molecular Weight: Smaller molecules easily pass through the pores of the dialysis filter.

- Low Protein Binding: If a drug is tightly latched onto proteins in the blood, it's too big and bulky to be pulled out.

- Small Volume of Distribution: The toxin needs to be circulating in the bloodstream, not hiding out in fat or other tissues where the dialyzer can't reach it.

- High Water Solubility: Since dialysis is an aqueous-based process, water-soluble toxins are much easier to remove.

The decision to dialyze for an intoxication isn't just about the substance itself, but also the severity of the poisoning. A patient with life-threatening complications like severe acidosis, seizures, or coma from a dialyzable toxin is a prime candidate for emergency hemodialysis.

Common Dialyzable Toxins and Drugs

Clinicians rely on a well-established list of substances that are known to be effectively cleared by dialysis. This knowledge is crucial in the emergency setting and is a high-yield topic for board exams.

The table below outlines some of the most common toxins you'll see managed with dialysis. Memorizing this list, especially the toxic alcohols and salicylates, is essential for both clinical practice and exam success.

Common Dialyzable Toxins and Drugs

| Substance | Clinical Indication for Dialysis | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Toxic Alcohols | Severe acidosis, end-organ damage (e.g., blindness) | Includes methanol (windshield fluid) and ethylene glycol (antifreeze). |

| Salicylates | Altered mental status, pulmonary edema, severe acidosis | Commonly known as aspirin; overdose can be life-threatening. |

| Lithium | Neurological toxicity (seizures, coma), very high levels | Dialysis is the primary method for rapidly removing lithium. |

| Valproic Acid | Coma, severe hyperammonemia, pancreatitis | An anticonvulsant that can cause severe toxicity in overdose. |

| Phenobarbital | Refractory hypotension, prolonged coma | A long-acting barbiturate that is effectively cleared with dialysis. |

These are the big players you should know. In these scenarios, dialysis doesn't just manage complications; it actively removes the poison fueling the crisis. By filtering the blood, it buys the body critical time to recover, preventing irreversible damage to the brain, heart, and other vital organs.

O for Overload When the Body Cannot Shed Excess Fluid

Imagine a city’s drainage system getting completely clogged after a torrential downpour. The streets would flood, causing widespread chaos and damage. This is a powerful analogy for fluid overload, or hypervolemia, one of the most urgent indications for dialysis.

When the kidneys fail, they lose their ability to produce urine and shed excess fluid. That fluid has to go somewhere, and it starts backing up in the body.

This isn't just about swollen ankles; it's a life-threatening emergency. The excess fluid accumulates in the most dangerous place possible: the lungs. This condition, known as pulmonary edema, is like drowning from the inside out. The heart, forced to pump against this overwhelming volume, begins to fail under the strain.

Recognizing When Fluid Overload Becomes an Emergency

The first line of defense against fluid overload is powerful diuretic medications, often called "water pills." But when the kidneys are severely damaged, they simply stop responding to these drugs. This diuretic resistance is a critical red flag that medical management is failing and the patient is heading toward a crisis.

Clinicians watch for clear signs that dialysis is needed immediately:

- Severe Shortness of Breath: The patient is struggling to breathe, often unable to lie flat without feeling like they are suffocating.

- Hypoxia: Oxygen levels in the blood drop to dangerously low levels because the fluid-filled lungs cannot perform gas exchange.

- Worsening Chest X-Ray: Imaging shows significant fluid accumulation, often described as a "white-out" appearance.

- Refractory to Diuretics: Despite high doses of medications like furosemide, the patient produces little to no urine.

When a patient is gasping for air and diuretics have failed, dialysis is no longer just an option—it is the only effective way to mechanically remove the excess fluid and restore respiratory function. It acts as a high-powered pump when the body’s own drainage system has shut down completely.

How Dialysis Provides Rapid Relief

Dialysis tackles fluid overload through a process called ultrafiltration. The dialysis machine creates a pressure gradient that literally pulls excess water directly out of the bloodstream, completely bypassing the non-functional kidneys. This process can remove liters of fluid in just a few hours, offering rapid and dramatic relief.

By mechanically offloading this fluid, dialysis takes immense pressure off the heart and lungs, allowing the patient to breathe easier almost immediately.

The growing need for such interventions reflects a global health trend. The worldwide demand for dialysis has seen significant growth, with the market valued at US$ 98.05 billion in 2023 and projected to climb to US$ 190.14 billion by 2033. You can explore more about these market trends in the global dialysis market research report.

U for Uremia: Recognizing the Signs of Systemic Toxicity

Finally, we arrive at Uremia, the last and arguably most encompassing of the indications for dialysis aeiou. This isn't just about a high Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) number on a lab report. Uremia is the full-blown systemic poisoning that takes hold when metabolic waste products build up and start wreaking havoc on the entire body.

Think of it like a major city drowning in its own uncollected garbage—eventually, every single system begins to shut down.

This distinction is absolutely critical. Our job as clinicians is to treat the patient, not the lab value. A high BUN in an otherwise stable patient might just need monitoring. But the moment severe uremic signs appear, it’s a clear signal that the body is being overwhelmed by toxins and needs immediate intervention.

The Hard Signs of a Uremic Emergency

The decision to pull the trigger on dialysis for uremia comes down to recognizing specific, life-threatening complications. We often call these the "hard signs" because they tell us the toxic buildup is causing significant, acute organ damage.

These are the red flags that demand immediate dialysis:

- Uremic Pericarditis: This is when the sac surrounding the heart becomes inflamed. It can lead to a dangerous buildup of fluid (pericardial effusion) and even cardiac tamponade. The classic bedside finding? Hearing a distinct "friction rub" with your stethoscope.

- Uremic Encephalopathy: The brain literally gets poisoned by uremic toxins. This manifests as confusion, lethargy, asterixis (that classic "flapping" tremor of the hands), and can rapidly progress to seizures or a coma.

- Bleeding Diathesis: Uremic toxins wreck platelet function. This impairment leads to uncontrollable or spontaneous bleeding that won't stop on its own.

The presence of any one of these—pericarditis, encephalopathy, or significant bleeding—is an absolute indication for urgent dialysis. It doesn't matter what the BUN or creatinine levels are at that point. This is the core of solid clinical reasoning; you're focusing on patient-oriented outcomes, not just isolated data points.

Dialysis as the Definitive Detox

When these severe symptoms emerge, medical management has reached its limit. Dialysis is the only definitive solution. It acts as an artificial kidney to physically filter out the uremic toxins that are poisoning the patient's systems.

Hemodialysis remains the most widely used form of dialysis globally, primarily because it's so efficient at rapidly clearing out toxins and excess fluid. This efficiency makes it the go-to modality for reversing acute, life-threatening uremic complications. By clearing the blood of these poisons, dialysis can quickly reverse encephalopathy, resolve pericarditis, and restore platelet function, effectively pulling the patient back from the brink.

Common Questions About Dialysis Indications

Moving the indications for dialysis aeiou mnemonic from a memorized list to real-world clinical judgment is where the rubber meets the road. It’s one thing to know the letters, but applying them in a high-pressure situation, especially on board exams, requires a deeper, more nuanced understanding.

Let's walk through some of the most common questions that come up when putting this framework into practice.

Do Specific Lab Numbers Trigger Dialysis?

One of the biggest misconceptions I see is the idea that a certain BUN or creatinine value automatically means a patient needs dialysis. This is simply false. The decision is almost always driven by the patient's clinical picture, not just a number on a lab report.

For example, you could have a stable patient with chronic kidney disease walking around with a sky-high creatinine, feeling perfectly fine. On the other hand, a patient with a much lower value who is confused and has a uremic pericardial friction rub needs dialysis right now. The "U" for Uremia is about the symptoms of waste product buildup, not just the number itself.

Urgent Versus Chronic Dialysis

So, what’s the difference between dialing the nephrologist for an emergency procedure versus a patient’s regularly scheduled treatment?

- Urgent Dialysis: This is a reactive, emergency intervention. We're stepping in to fix one of the life-threatening AEIOU conditions, like a dangerously high potassium or lungs filled with fluid.

- Chronic Dialysis: This is a proactive, scheduled treatment for patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). The goal is to prevent those emergencies from ever happening in the first place.

Think of it this way: urgent dialysis is the fire department rushing in to put out a raging fire. Chronic dialysis is the building’s sprinkler system, designed to prevent the fire from starting at all.

For healthcare professionals navigating these scenarios, clear and precise charting is critical. Using efficient medical documentation software can make a huge difference in capturing the clinical story accurately, especially when things are moving fast.

When Is CRRT Used Instead of Hemodialysis?

This is a key distinction, especially for ICU patients. Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy (CRRT) is essentially a gentler, marathon version of dialysis that runs 24 hours a day. It's reserved for critically ill, hemodynamically unstable patients.

Standard hemodialysis is like a sprint—it pulls off fluid and toxins very quickly. While efficient, this can cause a fragile patient's blood pressure to plummet. CRRT does the same job, just much more slowly, making it the safer bet for someone who is already on pressors or life support. Grasping these finer points is a core part of the USMLE content outline and a frequent topic on step exams.