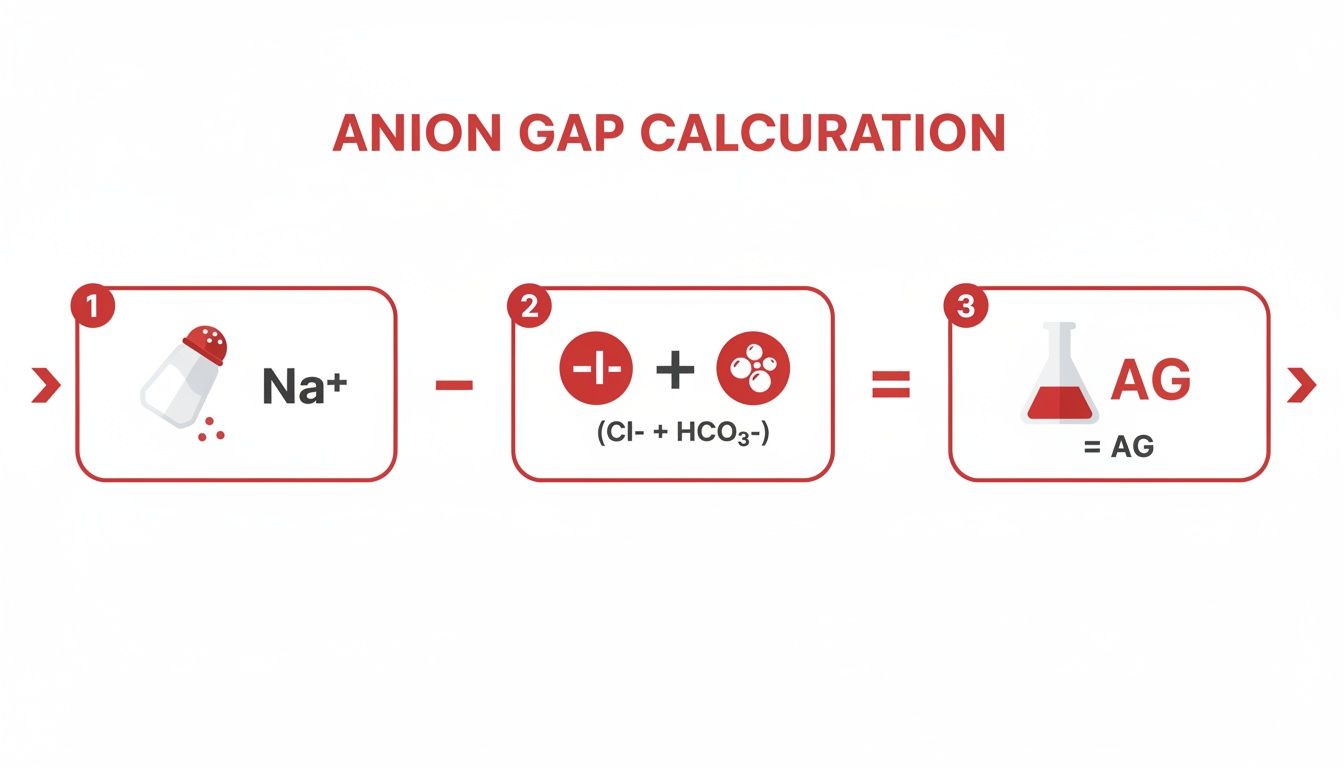

Calculating the anion gap is a surprisingly simple bit of math that gives you a powerful diagnostic clue. The formula you'll use every time is:

Anion Gap = [Na⁺] – ([Cl⁻] + [HCO₃⁻])

This calculation reveals the difference between the unmeasured anions (negative ions) and unmeasured cations (positive ions) floating around in your patient's blood. It's often the very first step you'll take when staring down a case of metabolic acidosis.

Why This Simple Formula is a Clinical Powerhouse

In the trenches of emergency medicine or the ICU, the anion gap is more than just a number on a lab report. Think of it as a quick screening tool that immediately helps you sort through the chaos of an acid-base imbalance.

When a patient rolls in with altered mental status, shortness of breath, or just looks critically ill, this calculation can instantly point you toward (or away from) a whole host of life-threatening conditions. Its main job is to help you differentiate between the two major types of metabolic acidosis, which completely changes your next move.

An elevated anion gap should make your ears perk up—it often triggers a hunt for things like toxic ingestions, ketoacidosis, or renal failure. Getting a handle on this is fundamental to building a solid differential diagnosis.

The Key Players in the Formula

To really nail the calculation and its interpretation, you have to know the three main electrolytes involved: Sodium (Na⁺), Chloride (Cl⁻), and Bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻). You’ll find these on any basic metabolic panel (BMP) or comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP).

Let's break down the components you'll be working with.

Key Components of the Anion Gap Calculation

This table summarizes the primary electrolytes used in the anion gap formula and their roles in maintaining the body's electrochemical balance.

| Electrolyte | Chemical Symbol | Charge | Primary Role in Calculation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium | Na⁺ | Positive (Cation) | The main measured cation in the blood. |

| Chloride | Cl⁻ | Negative (Anion) | A key measured anion that balances sodium. |

| Bicarbonate | HCO₃⁻ | Negative (Anion) | The primary buffer that helps regulate blood pH. |

Putting these electrolytes together gives you that critical snapshot of a patient's unmeasured ions.

Let's walk through a quick example. Say your patient's labs show a sodium of 137 mEq/L, chloride of 102 mEq/L, and bicarbonate of 24 mEq/L.

Plugging those into our formula:

Anion Gap = 137 – (102 + 24) = 11 mEq/L

An anion gap of 11 mEq/L falls squarely within the typical normal range of 4 to 12 mEq/L. It's important to know that this range is based on modern lab equipment using ion-selective electrodes. Back in the day (before the 1980s), the normal range was wider, from 8 to 16 mEq/L, because labs used a different technique called flame photometry. You can learn more about the history and application of this calculation on Wikipedia.

Mastering the Anion Gap Formulas

To really get a handle on the anion gap, you have to be comfortable with the math. It looks simple, but mastering the formulas means knowing which one to grab from your mental toolkit and how to plug in the numbers from a patient's lab report without hesitation. This isn't about memorizing for an exam; it's about building the muscle memory to do this crucial calculation quickly and accurately on the fly.

The standard formula is your workhorse—it's the one you'll use 99% of the time in clinical practice and on your boards. It elegantly boils things down to the three most critical electrolytes.

The Standard Formula:

Anion Gap = [Na⁺] – ([Cl⁻] + [HCO₃⁻])

This equation subtracts the major measured anions (Chloride and Bicarbonate) from the major measured cation (Sodium). What's left over is the "gap"—an estimate of the unmeasured anions like albumin, phosphate, and sulfate that are floating around.

The Potassium-Inclusive Formula

While you won't see it nearly as often, a second formula includes potassium (K⁺), another key cation.

The Potassium-Inclusive Formula:

Anion Gap = ([Na⁺] + [K⁺]) – ([Cl⁻] + [HCO₃⁻])

By adding potassium to the cation side, you technically get a more complete picture of the measured positive charges. But let's be realistic. Serum potassium levels are tiny (usually around 3.5-5.0 mEq/L), so its impact on the final number is minimal. This is exactly why most clinicians and institutions stick to the standard formula for the sake of simplicity and consistency.

This visual perfectly illustrates the straightforward flow of the standard anion gap calculation.

It’s a simple but powerful process: take the main positive ion, subtract the main negative ions, and see what the difference tells you.

Putting the Formulas into Practice

Let's walk through a scenario. A 57-year-old patient is brought in with altered mental status. You order a basic metabolic panel (BMP) and get these labs back:

- Na⁺: 145 mEq/L

- K⁺: 4.5 mEq/L

- Cl⁻: 105 mEq/L

- HCO₃⁻: 25 mEq/L

First, let's use the standard formula everyone defaults to.

Standard Calculation:

145 – (105 + 25) = 145 – 130 = 15 mEq/L

With a normal range typically between 4-12 mEq/L, a result of 15 mEq/L is definitely elevated. This immediately tells you the patient has a high anion gap metabolic acidosis (HAGMA) and points your differential diagnosis toward causes like ketoacidosis, lactic acidosis, or a toxic ingestion.

Now, just to see how it changes things, let's apply the potassium-inclusive formula to the same labs.

Potassium-Inclusive Calculation:

(145 + 4.5) – (105 + 25) = 149.5 – 130 = 19.5 mEq/L

As you can see, including potassium nudged the result higher. When this formula is used, its normal range is also adjusted upward, usually to about 8-16 mEq/L. So, in this case, both formulas correctly flag an elevated anion gap. This perfectly illustrates why the simpler, standard formula is almost always sufficient.

When Including Potassium Might Matter

So, is there ever a good reason to use the potassium formula? While rare, it can have some utility in specific situations where potassium is wildly out of whack.

- Severe Hypokalemia: If a patient has profound hypokalemia (e.g., K⁺ < 2.5 mEq/L), leaving it out could slightly underestimate the anion gap.

- Severe Hyperkalemia: Conversely, in a patient with life-threatening hyperkalemia (e.g., K⁺ > 7.0 mEq/L), adding it can provide a more precise picture of the cationic balance.

Ultimately, the most important thing is consistency. Whichever formula your institution uses, you must compare the result to the correct normal range for that specific formula. For your board exams and day-to-day practice, defaulting to the standard [Na⁺] – ([Cl⁻] + [HCO₃⁻]) formula is the accepted, expected, and most reliable approach.

Why You Must Adjust the Anion Gap for Albumin

Calculating the anion gap is a critical first step, but stopping there is a classic rookie mistake that can lead to a dangerous misinterpretation. A "normal" result might seem reassuring, but it can easily mask a life-threatening acidosis if you don’t account for the most abundant unmeasured anion in the blood: albumin.

This adjustment isn't just an academic exercise; it's a non-negotiable step for diagnostic accuracy, especially in critically ill patients.

Albumin is a negatively charged protein, and it contributes significantly to the baseline anion gap. In healthy individuals, normal albumin levels help establish the standard reference range of about 4-12 mEq/L. But when a patient's albumin level drops—a common scenario in sepsis, malnutrition, liver disease, or nephrotic syndrome—their baseline anion gap plummets right along with it.

This creates a serious clinical pitfall. A patient could be developing a nasty high anion gap metabolic acidosis (HAGMA), but their low albumin level artificially deflates the calculated number, making it look deceptively normal. Without correcting for this, you might miss the diagnosis entirely.

The Albumin Correction Formula

Fortunately, the fix is straightforward. The most widely used rule of thumb is a simplified version of the Figge-Jabor-Kazda equation, perfect for quick bedside calculations. This formula adjusts the anion gap based on how much the patient's albumin deviates from a normal level, typically set at 4.0 g/dL.

Corrected Anion Gap = Calculated Anion Gap + 2.5 * (4.0 – Measured Albumin)

Here’s how it works in practice: For every 1 g/dL drop in serum albumin below 4.0 g/dL, you can expect the normal anion gap to decrease by about 2.5 mEq/L. By adding this "missing" gap back to your calculated value, you reveal what the anion gap would be if the patient had normal albumin.

For a deeper dive, check out this guide on understanding the albumin normal range and its broader clinical implications.

A Real-World Clinical Scenario

Let's see this principle in action with a compelling case. Imagine you're managing a 68-year-old male with sepsis from pneumonia. He's lethargic, tachycardic, and hypotensive. You get back his initial labs:

- Na⁺: 138 mEq/L

- Cl⁻: 105 mEq/L

- HCO₃⁻: 23 mEq/L

- Albumin: 2.0 g/dL

First, you calculate the standard anion gap:

Calculated AG = 138 – (105 + 23) = 10 mEq/L

An anion gap of 10 falls comfortably within the normal range. At first glance, you might be tempted to rule out a HAGMA and start looking for other causes. But his albumin is critically low at 2.0 g/dL—that should immediately set off alarm bells.

Now, let’s apply the correction.

Corrected AG = 10 + 2.5 * (4.0 – 2.0)

Corrected AG = 10 + 2.5 * (2.0)

Corrected AG = 10 + 5 = 15 mEq/L

Suddenly, the picture changes entirely. The corrected anion gap of 15 mEq/L is clearly elevated, unmasking a hidden HAGMA. This new information immediately shifts your focus. What could be causing it? In a septic patient, lactic acidosis is always at the top of the list. You send a lactate level, which comes back elevated, confirming your suspicion.

This single adjustment transformed a "normal" lab value into a critical finding, directly guiding your resuscitation strategy. This is exactly why skipping the albumin correction is a risk you simply can't afford to take.

You’ve done the math, corrected for albumin, and now you’re staring at a single, crucial number. This is where the real diagnostic work begins—turning that number into a meaningful clinical direction.

Honestly, interpreting the anion gap is a core skill that separates the novice from the expert. It's the moment you move from just knowing the labs to understanding the patient. The value you calculated will sort your patient's metabolic acidosis into one of three buckets: high, normal, or (rarely) low, with each category pointing to a distinct set of problems. This is the essence of effective https://acemedboards.com/what-is-clinical-reasoning/—connecting the dots between the lab report and the person in front of you.

Decoding a High Anion Gap

When your corrected anion gap is elevated—typically climbing above 12 mEq/L—it signals a high anion gap metabolic acidosis, or HAGMA. This is a dead giveaway that an unmeasured acid has been added to the system. I like to think of it as a party crasher; some new, negatively charged substance has shown up, increasing the gap between the cations and anions we routinely measure.

Your job is to figure out who crashed the party. To keep the potential culprits organized, clinicians have relied on handy mnemonics for decades. The classic one most of us learned is MUDPILES:

- Methanol

- Uremia (chronic kidney failure)

- Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA)

- Propylene glycol

- Isoniazid, Iron

- Lactic acidosis

- Ethylene glycol

- Salicylates

More recently, a newer mnemonic, GOLDMARK, has gained traction because it better reflects the common causes we see in modern clinical practice. It's a bit more current and arguably more useful day-to-day.

- Glycols (ethylene and propylene)

- Oxoproline (from chronic acetaminophen use)

- L-Lactate (the most common cause of HAGMA)

- D-Lactate (rare, seen in short-gut syndrome)

- Methanol

- Aspirin (salicylates)

- Renal failure (uremia)

- Ketoacidosis (diabetic, alcoholic, starvation)

Let's make this real. You have a patient with uncontrolled type 1 diabetes presenting with altered mental status. You run the labs, and their calculated anion gap is 24 mEq/L. This screams Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA). The "gap" is being filled by unmeasured ketoacids like beta-hydroxybutyrate.

In HAGMA, the core problem is the addition of an unmeasured acid. The body tries to buffer this new acid by consuming bicarbonate, which is why the HCO₃⁻ level drops. The key clue is that the chloride level usually stays right where it is.

When the Anion Gap Is Normal

Finding a normal anion gap in a patient with metabolic acidosis can be just as informative. We call this a normal anion gap metabolic acidosis, or NAGMA. In this scenario, there's no new, unmeasured acid being added to the mix.

Instead, the acidosis is caused by a direct loss of bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻) from the body.

Think of it as a balancing act. To maintain electrical neutrality when all that negatively charged bicarbonate is lost, the kidneys compensate by holding onto another negative ion: chloride. This is why NAGMA is also known as hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis. The chloride level goes up as the bicarbonate level goes down, keeping the gap deceptively normal.

A classic mnemonic for the causes of NAGMA is HARDUP:

- Hyperalimentation (TPN)

- Acetazolamide

- Renal Tubular Acidosis (RTA)

- Diarrhea (by far the most common cause)

- Ureteroenteric fistula

- Pancreatic fistula

Diarrhea is the textbook example. The GI tract can shed huge amounts of bicarbonate-rich fluid, leading directly to acidosis. The kidneys kick in, hold onto chloride to maintain charge balance, and the anion gap stays put.

Unpacking a Low Anion Gap

Seeing a low anion gap (less than 3 mEq/L) is pretty uncommon, happening in less than 1% of cases. It should immediately make you suspicious. Before you start digging for a rare diagnosis, your first thought should always be lab error.

But if it's a true low anion gap, it can point to some important pathologies. This usually happens when there's a drop in unmeasured anions (most often severe hypoalbuminemia) or, more interestingly, an increase in unmeasured cations.

Conditions like multiple myeloma can produce large quantities of positively charged proteins (paraproteins), which effectively narrow the gap. Similarly, things like severe hypercalcemia or hypermagnesemia add unmeasured positive charges to the blood, throwing off the calculation.

High Anion Gap vs Normal Anion Gap Metabolic Acidosis

Distinguishing between HAGMA and NAGMA is a fundamental step in working up metabolic acidosis. A quick look at the core differences can help solidify your understanding and guide your next diagnostic steps. For a broader look at making sense of diagnostic data, this guide on general principles for interpreting lab results can be a useful resource.

This table provides a quick reference to distinguish between the two major types of metabolic acidosis.

| Feature | High Anion Gap Metabolic Acidosis (HAGMA) | Normal Anion Gap Metabolic Acidosis (NAGMA) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Problem | Addition of an unmeasured acid (e.g., lactate, ketones). | Loss of bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻). |

| Chloride Level | Typically normal. | Typically elevated (hyperchloremic). |

| Core Mechanism | Anion gap is "filled" by a new, unmeasured anion. | Chloride is retained to balance the loss of bicarbonate. |

| Classic Cause | Lactic acidosis, Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA). | Diarrhea, Renal Tubular Acidosis (RTA). |

Ultimately, the anion gap is more than just a number—it’s a powerful diagnostic tool that tells a story about the patient's physiology. Mastering its interpretation will sharpen your clinical acumen and lead you to the right diagnosis faster.

Clinical Pitfalls and High-Yield Tips

Moving beyond the basic formulas, true mastery of the anion gap comes from navigating the tricky scenarios you'll encounter on the wards and in board exam questions. This is where subtle clues can completely change your diagnosis. Recognizing these pitfalls and applying high-yield strategies will sharpen your clinical decision-making when every detail matters.

One of the most powerful—and often overlooked—tools is the delta ratio, sometimes called the delta gap. This quick calculation helps you uncover mixed acid-base disorders that a standard anion gap might otherwise hide.

Unmasking Mixed Disorders with the Delta Ratio

The delta ratio compares the change in the anion gap (ΔAG) to the change in bicarbonate (ΔHCO₃⁻). In simple terms, it answers a critical question: Is the drop in bicarbonate proportional to the rise in the anion gap?

Delta Ratio = (Calculated AG – 12) / (24 – Measured HCO₃⁻)

We use 12 as the normal anion gap and 24 as the normal bicarbonate. The ratio you get tells a story about what's really going on.

- A ratio between 1.0 and 2.0 points to a pure high anion gap metabolic acidosis (HAGMA). For every one point the anion gap climbs, the bicarbonate falls by roughly one point. This is the clean, uncomplicated picture you'd expect in something like straightforward DKA or lactic acidosis.

- A ratio below 1.0 screams that a normal anion gap metabolic acidosis (NAGMA) is also present. This means the bicarbonate has dropped way more than you'd expect for the rise in the anion gap. The classic scenario is a DKA patient who also has severe diarrhea—they're losing bicarbonate from two different sources at once.

- A ratio above 2.0 strongly suggests a concurrent metabolic alkalosis is muddying the waters. In this case, the bicarbonate level is higher than it should be for the degree of HAGMA. Think of a DKA patient who has also been vomiting profusely, losing gastric acid and driving their bicarbonate up.

The Albumin Trap: A Deceptively Normal Gap

We've already touched on correcting for albumin, but this point is so critical it's worth flagging as a major clinical pitfall. A "normal" anion gap of 10 in a patient with an albumin of 2.0 g/dL isn't normal at all—it’s a massive red flag for a hidden HAGMA.

Always correct the anion gap for albumin, especially in your sickest patients—the critically ill, malnourished, or septic. Forgetting this step is one of the most common and dangerous errors you can make. The corrected value often reveals the true metabolic picture.

Watch Out for Lab Errors and Interferences

Before you launch into a complex diagnostic workup for a bizarre result, take a breath and consider the possibility of a lab error. If a value just doesn't fit the clinical picture, your first move should be to ask for a repeat.

A perfect example is a negative anion gap. While rare, it's almost always due to an error or a specific substance interfering with the test.

- Bromide Toxicity: The lab analyzer gets confused and misreads bromide as chloride, falsely jacking up the chloride level and pushing the anion gap into negative territory.

- Severe Hyperlipidemia: Extremely high lipid levels can throw off the electrolyte measurement process.

- Unmeasured Cations: The presence of abnormal positively charged proteins, like in multiple myeloma, can also artifactually lower the gap.

If you see a negative anion gap, your first thought shouldn't be a rare disease. It should be to question the result and consider these specific interferences.

High-Yield Board Exam Tips

When you're staring down an exam question, a systematic approach is your best friend. These high-yield tips will help you cut through the noise, analyze the data quickly, and lock in the correct diagnosis.

- Calculate the anion gap first. Always. If a patient presents with metabolic acidosis, this is your initial branching point. Don't skip it.

- Correct for albumin immediately. This is a classic exam trick designed to see if you're being thorough. Don't fall for it.

- Use the delta ratio for any HAGMA. This is absolutely essential for spotting the mixed disorders that examiners love to test.

- Connect the gap to the cause. A high anion gap in a patient with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) is likely from uremia, a crucial piece of information when you're thinking about treatment. For a refresher, you can review the common indications for dialysis and see how uremia fits into the clinical picture.

- Don’t forget the osmolal gap. In any case of suspected toxic ingestion (think methanol or ethylene glycol), calculating the osmolal gap alongside the anion gap is a non-negotiable diagnostic step. An elevated anion gap plus an elevated osmolal gap is highly suggestive of toxic alcohol poisoning.

Anion Gap FAQs

Even after you've got the formulas down, some questions about the anion gap seem to pop up constantly in the clinic and during exam prep. Getting straight answers to these common sticking points is the key to using this tool confidently when a patient is in front of you. Let's dig into a few of the most frequent ones.

Why Is Potassium Usually Excluded From the Formula?

You've probably noticed that potassium is almost always left out of the anion gap calculation, and there’s a good reason for that. Potassium's concentration in the blood is pretty low, typically hanging out between 3.5 and 5.0 mEq/L. When you compare that to sodium, which is usually up around 140 mEq/L, you can see that potassium’s contribution to the total cation count is tiny.

Including it just adds another step for a number that barely moves the needle. For simplicity, consistency, and quick bedside calculations, the standard formula [Na⁺] – ([Cl⁻] + [HCO₃⁻]) is what everyone uses. It gives you a reliable, actionable result for virtually all diagnostic situations.

Can the Anion Gap Be Negative and What Does It Mean?

Yes, an anion gap can be negative, but it's incredibly rare and should be an immediate red flag. A negative result is almost always a sign of a lab error or a major underlying issue messing with the measurements.

Your first move when you see a negative anion gap shouldn’t be to diagnose some obscure disease—it should be to question the result. Repeating the labs is the critical first step while you think through the possibilities.

The most common culprits for a true negative anion gap include:

- Bromide Toxicity: The lab analyzer can get fooled and read bromide as chloride, which artificially jacks up the chloride value and pushes the gap down.

- Severe Hyperlipidemia: Extremely high levels of lipids in the blood can throw off the electrolyte measurement process.

- Unmeasured Cations: Certain conditions, like multiple myeloma, can crank out large amounts of positively charged proteins (paraproteins), which effectively narrow or even reverse the gap.

How Does the Delta Gap Help Diagnose Mixed Disorders?

The delta gap, also known as the delta ratio, is a more advanced tool that's absolutely crucial for sniffing out complex, mixed acid-base disorders that a simple anion gap calculation might miss. It works by comparing the change in the anion gap to the change in bicarbonate.

A ratio between 1.0 and 2.0 usually points to a pure high anion gap metabolic acidosis. But if the ratio is below 1.0, it suggests a co-existing normal anion gap metabolic acidosis is also going on—meaning the bicarb loss is way more than you'd expect. On the flip side, a ratio above 2.0 is a strong clue that a metabolic alkalosis is happening at the same time, because the bicarbonate is higher than it should be. It’s a vital second step to get the full clinical picture.

Mastering these concepts is a game-changer for your exams and clinical rotations. For personalized guidance and strategies to ace your boards, Ace Med Boards offers expert one-on-one tutoring tailored to your needs. Visit us at https://acemedboards.com to schedule a free consultation and take your performance to the next level.