When you get down to it, cardiac physiology really boils down to two key forces: preload and afterload. Think of preload as the tension in a slingshot just before you let go—it's the initial stretch on the heart muscle. Afterload is the resistance that slingshot's pebble faces as it flies, like wind resistance—it’s the force the heart has to push against.

Getting a solid handle on these two concepts is non-negotiable for understanding how the heart works.

Decoding Preload and Afterload for Exam Success

For medical students, preload and afterload aren't just vocabulary. They are the fundamental principles that explain nearly everything about the heart, from normal function to complex disease states. If you want to nail clinical scenarios on your board exams, you have to master these concepts.

They describe the push-and-pull forces acting on the ventricles during every single heartbeat, dictating how much blood gets pumped out. Once you have a strong mental model of this dynamic, topics like heart failure and valvular disease suddenly become much more intuitive.

Core Concepts Explained

Preload is all about the stretch. Specifically, it's the initial stretching of the cardiac muscle cells right before they contract. This is a direct application of the Frank-Starling mechanism, a concept that's been foundational since the early 1900s. In the clinic, we measure this using proxies like left ventricular end-diastolic volume (EDV) or pressure (LVEDP).

Essentially, preload answers a simple question: How full is the ventricle just before it squeezes?

Afterload, on the other hand, is the pressure the ventricle has to generate to actually push blood out into the body. It’s the wall stress required to pop open the aortic valve and overcome the resistance in the circulatory system. This force answers the question: How hard does the heart have to push to get the blood moving?

The main things determining afterload are systemic blood pressure and how stiff or compliant the major arteries are.

Think of it this way: Preload is a volume problem—how much blood is filling the heart. Afterload is a pressure problem—what resistance is the heart ejecting against. Both have to be in balance for the heart to work efficiently.

To make these concepts stick for your exams, seeing them side-by-side is a huge help. This table quickly breaks down the key differences, what determines them, and how we measure them clinically. Think of this as a high-yield framework for building the foundation you'll need for complex USMLE questions. For more high-yield topics, check out our complete USMLE content outline.

Preload vs Afterload at a Glance

Here’s a quick summary to help you differentiate these two critical concepts at a glance.

| Concept | Preload | Afterload |

|---|---|---|

| Core Definition | The stretch on the ventricular muscle at the end of diastole (filling). | The force the ventricle must overcome to eject blood during systole (contraction). |

| Primary Determinants | Venous return, blood volume, and ventricular compliance. | Systemic vascular resistance (SVR) and aortic pressure. |

| Key Clinical Measures | Central Venous Pressure (CVP), Pulmonary Capillary Wedge Pressure (PCWP). | Systemic Vascular Resistance (SVR), Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP). |

Getting these distinctions down is the first step. Next, we'll dive into how they directly impact cardiac output and what happens when they go wrong.

Mastering Preload: The Heart's Filling Pressure

To really get a handle on preload, forget the textbook definition for a moment. Instead, picture the heart's ventricle as a simple rubber band. Preload is the amount of stretch on that rubber band right before it snaps back—the tension on the muscle fibers at the very end of diastole, just before contraction.

The more you stretch that rubber band (within reason), the more forcefully it recoils. The heart works the exact same way. This elegant, self-regulating relationship is called the Frank-Starling mechanism.

When more blood returns to the heart, the ventricular walls stretch more. This increased stretch leads to a stronger, more powerful contraction, ejecting a larger stroke volume. It’s the heart’s brilliant way of automatically matching its output to whatever the body sends its way, like ramping things up during exercise. But just like a rubber band, there's a limit. Overstretch it, and it loses its snap—a concept that becomes critical in disease.

Key Determinants of Preload

So, what actually controls this stretch? Preload isn't just one number; it's a dynamic state influenced by a few key physiological factors. Getting these down is essential for diagnosing and managing cardiac conditions.

The three main players determining preload are:

- Venous Return: This is simply the rate of blood flow coming back to the heart. Anything that boosts venous return—like giving IV fluids or venous constriction—will crank up the preload.

- Total Blood Volume: It's a simple volume game. More blood in the tank means more is available to fill the heart. This is why dehydration drops preload, while fluid overload from kidney failure sends it soaring.

- Ventricular Compliance: Think of this as the "stretchiness" of the ventricle itself. A stiff, non-compliant ventricle, like one you'd see after years of chronic hypertension, can't relax and fill properly. This means you can have sky-high filling pressures (and thus high preload) even with normal blood volume.

How We Measure Preload Clinically

In the real world, we can’t exactly measure the stretch on individual cardiac muscle cells. So, we rely on stand-ins, or proxies, that tell us about the filling pressures inside the heart.

For the right side of the heart, we measure the Central Venous Pressure (CVP). For the more clinically critical left side, we use the Pulmonary Capillary Wedge Pressure (PCWP). These pressures give us a vital window into a patient’s volume status and guide our decisions, like whether to give diuretics or more fluids. These concepts are bread-and-butter for exams, frequently showing up among USMLE Step 1 high-yield topics.

Clinical Pearl: A patient rolling into the ER with decompensated heart failure will almost always have a high CVP and PCWP. This tells you their preload is pathologically elevated, causing fluid to back up into the lungs (pulmonary edema) and the body (peripheral edema).

Preload in Pathological States

The real value of understanding preload comes when you apply it to disease states. In heart failure, the kidneys often go into panic mode and retain sodium and water, trying to "help" by increasing blood volume to improve cardiac output.

At first, this compensation works via the Frank-Starling mechanism. But soon, the ventricle becomes chronically overstretched and overwhelmed. This excessive preload is the direct cause of congestion, leading to classic symptoms like shortness of breath and swollen legs.

On the flip side, conditions that cause massive fluid loss—like hemorrhage or severe dehydration—create a state of dangerously low preload. Not enough blood is returning to the heart, so the ventricles barely stretch. The result? Cardiac output plummets, and the patient spirals into shock.

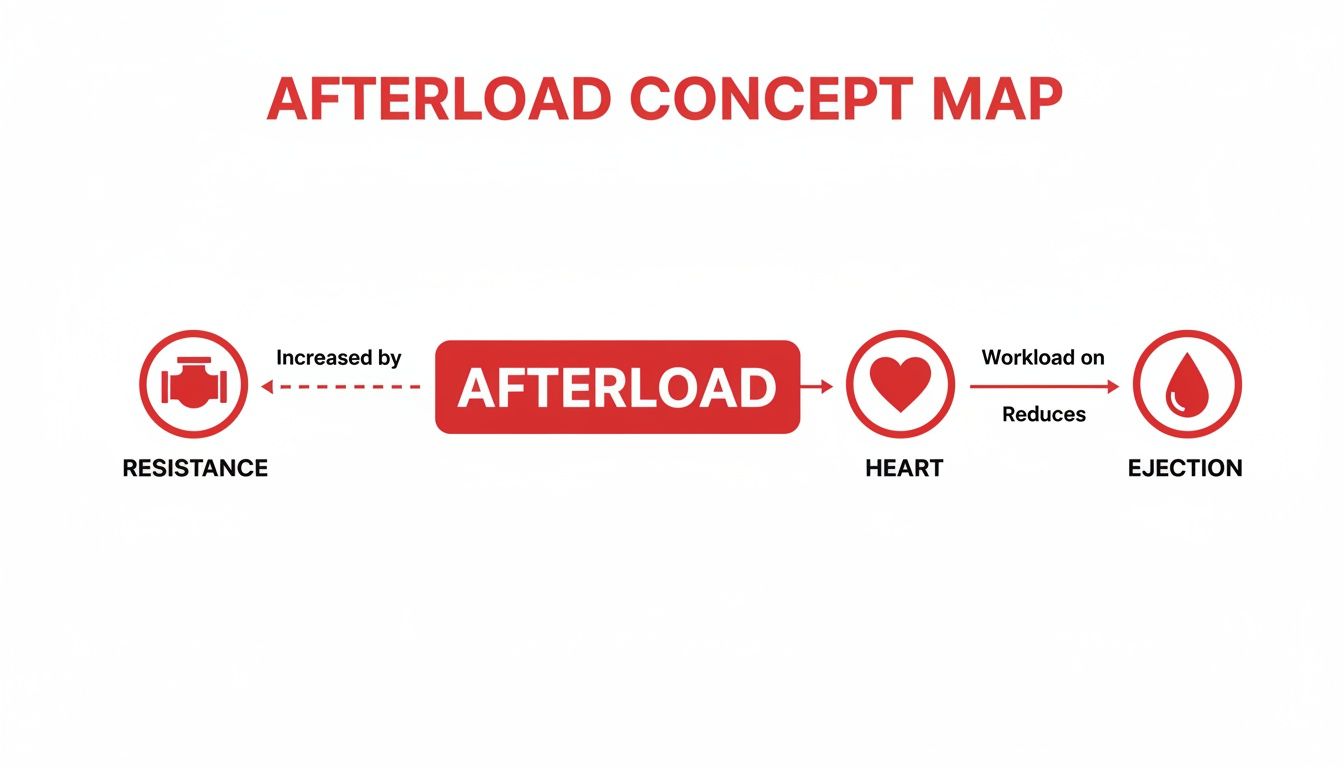

Breaking Down Afterload: The Resistance to Ejection

If preload is all about the stretch, then afterload is all about the squeeze. Think of it as the force the heart's ventricles must generate just to push blood out into the great vessels—the aorta and the pulmonary artery. Right after the aortic valve clicks open, the ventricle comes face-to-face with this resistance.

A great analogy is trying to open a heavy, spring-loaded door. The force you have to exert to even get the door to budge? That's the afterload. For the left ventricle, that "door" is the combined pressure of the blood already sitting in the aorta and the resistance from every single blood vessel in the systemic circulation.

This concept map breaks down how resistance directly fuels afterload, which then impacts the heart's workload and how effectively it can eject blood.

As you can see, when resistance goes up, afterload follows, forcing the heart to work much harder. The consequence? A drop in how much blood it can actually pump out with each beat.

The Main Drivers of Afterload

So, what makes that door harder to push open? It really boils down to two key factors. Nailing these is crucial for diagnosing preload and afterload issues, especially on exams.

- Systemic Vascular Resistance (SVR): This is the sum total of resistance from all the blood vessels in the body. When arteries clamp down (vasoconstriction), SVR skyrockets, and the heart has to overcome a much bigger hurdle.

- Aortic Pressure: This is simply the pressure inside the aorta that the left ventricle has to overpower to get the aortic valve to open. Conditions like chronic high blood pressure put this number on a steady incline.

In essence, afterload is the wall of resistance the ventricle slams into during ejection. We often use SVR or aortic pressure as a clinical stand-in for it. Any spike in afterload leaves more blood behind in the ventricle (increasing end-systolic volume) and shrinks the stroke volume. You can see this play out beautifully on pressure-volume loops, as explored in this detailed overview on StatPearls.

High-Afterload Clinical Scenarios

When afterload stays high for too long, it puts a tremendous, chronic strain on the heart muscle. To cope, the heart bulks up—a process called hypertrophy. But if the strain continues, this adaptation eventually fails, leading straight to heart failure.

You’ll see high-afterload states pop up in a few common clinical pictures:

- Chronic Hypertension: Persistently high blood pressure means the ventricle is in a constant battle against elevated resistance. It's like making the heart lift heavy weights, 24/7.

- Aortic Stenosis: Here, the aortic valve itself is stiff and narrowed. The ventricle has to generate immense pressure just to squeeze blood through that tiny opening, which massively cranks up the afterload.

Clinical Pearl: The inverse relationship between afterload and stroke volume is a core concept you absolutely have to know. As afterload rises, the speed at which the heart's muscle fibers can shorten goes down. This means the ventricle just can't eject blood as quickly or as completely, causing stroke volume to plummet.

Low-Afterload States and Interventions

On the flip side, a low afterload means the heart is meeting very little resistance. While that might sound like a good thing, it's often a red flag for a serious problem.

The textbook example is septic shock. A massive, body-wide infection triggers widespread vasodilation, causing systemic vascular resistance to collapse. The heart can pump blood out with incredible ease, but because the "pipes" are so wide open, blood pressure drops to dangerously low levels.

From a treatment standpoint, we often aim to reduce pathologically high afterload to give a struggling heart a break. We use vasodilators—medications that relax the blood vessels—to lower SVR and ease the heart's workload. Drugs like ACE inhibitors and ARBs are mainstays in treating heart failure and hypertension for this very reason: they are potent afterload reducers.

Visualizing Cardiac Function with Pressure-Volume Loops

A P-V loop plots the pressure inside the left ventricle (y-axis) against the volume of blood it's holding (x-axis). As the heart beats, it traces a counter-clockwise loop through the four phases of the cardiac cycle. Once you master reading these loops, abstract concepts become concrete, visual tools you can use to diagnose heart problems in seconds.

Deconstructing the Normal P-V Loop

Let's walk through a normal cardiac cycle, one phase at a time, to see what the P-V loop is really showing us. Each corner of the loop marks a critical event, like a valve snapping open or shut.

Phase 1 (A → B) Ventricular Filling: The cycle kicks off at point A when the mitral valve opens. Blood flows from the atrium into the relaxed ventricle, causing the volume to shoot up with only a small increase in pressure. This phase ends at point B, which marks the end-diastolic volume (EDV)—the maximum amount of blood the ventricle will hold, and our direct measure of preload.

Phase 2 (B → C) Isovolumetric Contraction: At point B, the mitral valve slams shut. Now the ventricle starts to squeeze, but since the aortic valve is still closed, no blood can escape. The volume stays perfectly constant while the pressure inside the ventricle skyrockets.

Phase 3 (C → D) Ventricular Ejection: At point C, the pressure inside the ventricle finally becomes greater than the pressure in the aorta, forcing the aortic valve to pop open. Blood is powerfully ejected into the circulation, and the ventricular volume plummets. The peak pressure hit during this phase is a reflection of the afterload the heart is fighting against.

Phase 4 (D → A) Isovolumetric Relaxation: At point D, the aortic valve closes. The ventricle relaxes, and the pressure falls off a cliff, all while the volume stays the same. The blood that's left over at this point is the end-systolic volume (ESV).

Key Takeaway: The width of the P-V loop represents the stroke volume (SV), which is simply EDV minus ESV. A wider loop means a bigger stroke volume and a more powerful, efficient heartbeat.

How Preload Changes the Loop's Shape

So, what happens when we mess with preload? Imagine giving a patient an IV fluid bolus. This increases the amount of blood returning to the heart, which directly increases preload.

This has a very predictable effect on the P-V loop:

- The ventricle fills with more blood, so the end-diastolic volume (EDV) at point B increases.

- This pushes the entire loop to the right.

- Because of the Frank-Starling mechanism, that extra stretch leads to a stronger contraction, which pumps out more blood and increases the stroke volume.

- The end result? The loop gets wider.

On the flip side, if a patient is hemorrhaging, their preload drops. This would shift the loop to the left and make it narrower, showing a smaller stroke volume.

How Afterload Changes the Loop's Shape

Now let's consider increased afterload, like what you’d see in a patient with aortic stenosis or uncontrolled hypertension. This makes it much harder for the ventricle to push blood out.

This creates a completely different set of changes on the loop:

- The ventricle has to generate a much higher pressure just to get the aortic valve to open.

- This makes the entire loop taller.

- Since it's harder to eject blood, less of it gets pumped out, leaving a larger end-systolic volume (ESV).

- This combination of higher pressure and reduced ejection makes the loop both taller and narrower.

If we were to give a vasodilator to reduce afterload, we’d see the opposite effect. The loop would become shorter and wider, signaling a much-improved stroke volume. By understanding these visual shifts, you can instantly diagnose the underlying problem in any clinical scenario you see on an exam.

Changes in preload, afterload, and contractility create distinct and predictable shifts in the P-V loop. The table below summarizes these key transformations, which are essential for interpreting cardiac physiology on exams.

| Parameter Change | Effect on EDV | Effect on ESV | Effect on Stroke Volume | Loop Appearance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased Preload | ↑ Increases | Unchanged | ↑ Increases | Shifts right, becomes wider |

| Increased Afterload | Unchanged | ↑ Increases | ↓ Decreases | Shifts up, becomes narrower |

| Increased Contractility | Unchanged | ↓ Decreases | ↑ Increases | Shifts left, becomes wider |

Mastering how each variable independently alters the loop is the key. In clinical practice, these changes often happen together, but for exams, you need to know what an isolated increase or decrease in each one looks like.

Applying Preload and Afterload to Clinical Scenarios

Understanding the theory of preload and afterload is one thing. Applying it to a real-life patient vignette is where you truly show you've mastered the concept. This is where abstract physiology crashes into clinical reality.

On your exams, you won't just get asked for definitions. You'll need to diagnose conditions based on their unique hemodynamic signatures. Let's break down how these forces go haywire in common diseases so you can spot the patterns in any clinical scenario.

Heart Failure: The Classic Imbalance

Heart failure is the ultimate example of preload and afterload going wrong. It's a complex syndrome where the heart just can't pump enough blood to meet the body's demands, kicking off a vicious cycle of compensation that only makes things worse.

Systolic Heart Failure (HFrEF)

In systolic heart failure, or heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), the core problem is a weak, boggy ventricle that can't squeeze effectively.

- Elevated Preload: Because the heart can't pump blood forward, it backs up. This traffic jam increases the end-diastolic volume (EDV), leading to pathologically high preload. This is the direct cause of congestive symptoms like fluid in the lungs and swollen legs.

- Elevated Afterload: The body senses low cardiac output and panics. It activates compensatory systems like the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), causing widespread vasoconstriction. This dramatically increases systemic vascular resistance (SVR) and, therefore, afterload, forcing an already weak heart to work against a clamped-down system.

Diastolic Heart Failure (HFpEF)

In diastolic heart failure, or heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), the ventricle is thick and stiff. The squeeze is fine, but it can't relax and fill properly.

- Elevated Preload: The stiff ventricular wall means that even a normal amount of blood creates sky-high pressure inside the chamber. This results in a high preload state characterized by congestion, even if the ventricle isn't overly stretched.

- Afterload's Role: Many patients with HFpEF also have chronic hypertension—a primary cause of that ventricular stiffness. This means they are often struggling against high afterload as well.

Valvular Diseases: Creating Hemodynamic Chaos

Valvular heart diseases create mechanical problems that directly mess with preload and afterload, making them classic exam scenarios.

Aortic stenosis is the quintessential high-afterload state. The narrowed valve acts like a bottleneck, forcing the left ventricle to generate immense pressure just to push blood out. This sustained pressure overload causes the ventricular wall to thicken (concentric hypertrophy) as it tries to adapt.

Conversely, leaky valves are all about volume overload.

- Aortic Regurgitation: When the aortic valve leaks, blood flows back into the left ventricle during diastole. This returning blood adds to the normal filling from the atrium, creating a massive increase in end-diastolic volume and, therefore, a chronically high preload.

- Mitral Regurgitation: Here, blood leaks backward from the ventricle into the atrium during systole. This forces the ventricle to handle much more volume on the next beat just to maintain forward flow, also leading to a state of high preload.

The Unique Signatures of Shock States

Shock is a state of life-threatening circulatory failure. The different types of shock can be distinguished by their unique preload and afterload profiles—a super high-yield area for exam questions. For a deeper dive, our guide to the Internal Medicine Shelf exam covers these topics in detail.

- Cardiogenic Shock: The heart itself fails as a pump, maybe after a massive heart attack. Preload skyrockets as blood backs up, and afterload increases due to compensatory vasoconstriction. The profile is high preload, high afterload.

- Septic Shock: A massive infection triggers widespread vasodilation. Systemic vascular resistance plummets, creating a state of profoundly low afterload. Preload can be low initially due to leaky capillaries but often becomes high after aggressive fluid resuscitation. The classic picture is low afterload, high preload.

Targeting Preload and Afterload with Medications

Okay, so we've covered the theory. Now let's talk about putting it into practice with pharmacology. In the real world of clinical medicine, we’re constantly using medications to tweak a patient's hemodynamics. Knowing which drug hits preload, which one targets afterload, and which affects both is absolutely critical—not just for managing serious cardiac conditions, but for crushing your exam questions, too.

Most of our pharmacologic strategies boil down to one simple goal: making the heart's job easier. For a failing heart that’s either drowning in fluid (high preload) or straining against a clamped-down vascular system (high afterload), the right medication can be a lifesaver.

Medications That Primarily Reduce Preload

When a patient is fluid overloaded, like in decompensated heart failure, our main objective is to reduce the filling pressure—the preload. Think of it like letting some air out of an overinflated tire; you’re reducing the strain on its walls.

Our go-to tools for this are:

- Diuretics (e.g., Furosemide): These are the absolute workhorses for preload reduction. They tell the kidneys to kick out more sodium and water, which directly shrinks the total blood volume. Less volume means less venous return to the heart, and voilà, lower preload.

- Venodilators (e.g., Nitroglycerin): These drugs relax the veins, essentially making them bigger "containers" for blood. This causes "venous pooling," meaning more blood stays out in the periphery and less returns to the heart with each beat. This effectively drops the end-diastolic pressure and helps relieve congestion.

Medications That Primarily Reduce Afterload

What about when the heart is struggling against massive resistance? In that case, we need to open up the arterial "pipes." By reducing this resistance, or afterload, we allow the ventricle to eject blood far more easily, which in turn boosts stroke volume and cardiac output.

The key players here are:

- Arterial Vasodilators (e.g., Hydralazine): These medications directly relax the smooth muscle lining our arteries, causing them to widen. This brings down the systemic vascular resistance (SVR) that the left ventricle has to pump against.

- ACE Inhibitors (e.g., Lisinopril) & ARBs (e.g., Losartan): This class of drugs is a cornerstone of heart failure therapy. They work by blocking the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), which prevents the formation of the potent vasoconstrictor angiotensin II. The result? A major drop in afterload. Grasping how different drugs for heart failure work on these forces is crucial for applying these concepts to patient care.

Clinical Pearl: In a patient with systolic heart failure, you'll often see a combination of a nitrate (to reduce preload) and hydralazine (to reduce afterload). This duo provides powerful hemodynamic support by tackling both the volume problem and the pressure problem that are straining the weakened ventricle.

Medications That Increase Afterload

Sometimes, the issue isn't too much resistance—it's far too little. In states like septic shock, widespread vasodilation leads to a catastrophic drop in blood pressure. The goal here is actually to increase afterload to restore blood flow to the brain, kidneys, and other vital organs.

This is where vasopressors like Norepinephrine come in. These drugs trigger potent arterial vasoconstriction, dramatically increasing SVR and, as a result, afterload. This is how we crank the blood pressure back up to a level that can sustain life. Mastering these pharmacological principles is one of the most important USMLE Step 2 CK high-yield topics you'll face.

High-Yield Questions on Preload and Afterload

Let's dig into some of the trickier questions about preload and afterload that love to show up on board exams. Nailing these distinctions is often what separates a good score from a great one because they test if you can apply core physiology to real clinical scenarios.

Wall Stress vs Afterload

Many students just equate afterload with blood pressure, but it's more precise—and much higher-yield—to think of it as ventricular wall stress during ejection. This isn't just semantics; it's a critical distinction.

Remember the Law of Laplace (Stress ∝ Pressure × Radius / Thickness)? This simple formula shows that afterload isn't just about the pressure the heart pumps against. A dilated, failing ventricle has a much larger radius. This means it experiences massively higher wall stress—and therefore higher afterload—even if the patient's blood pressure is totally normal. This is the vicious cycle of heart failure in a nutshell.

Contractility's Relationship with Preload and Afterload

Think of contractility (inotropy) as the raw horsepower of the heart muscle. It's an intrinsic property, completely independent of whatever loading conditions you throw at it. It's just how strong the cardiac muscle cells are.

If you give a patient an epinephrine infusion, you're increasing contractility. The heart will now contract more forcefully at any given preload and afterload. On a P-V loop, this shifts the end-systolic pressure-volume relationship (ESPVR) up and to the left, resulting in a smaller end-systolic volume and a much bigger stroke volume.

These three factors—preload, afterload, and contractility—are the absolute core trio that determines cardiac output.

Key Takeaway: Contractility is the engine's power, preload is the amount of fuel in the tank, and afterload is how steep of a hill the car has to climb. They all work together, but they are fundamentally different variables.

Can High Preload and Low Afterload Coexist

Absolutely, and when they do, you get a classic clinical picture: septic shock. Understanding this is a must-know for exams. We cover similar complex scenarios in our guides on CCS exam preparation.

In sepsis, a massive inflammatory cascade causes widespread vasodilation, which makes systemic vascular resistance (SVR) plummet. This creates a state of profoundly low afterload. At the same time, we're pumping the patient full of IV fluids and their capillaries are leaky, which can lead to high filling pressures (a high CVP). This creates high preload.

This specific combination—low resistance and high volume—is what gives you the "warm shock" presentation that's so characteristic of distributive shock.

At Ace Med Boards, we specialize in breaking down complex topics like these to help you excel. Our expert one-on-one tutoring can provide the personalized strategies you need to master high-yield concepts and achieve your target score. Learn more at https://acemedboards.com.